PROCESS

With a commission, you and your maker are entering into a relationship that will, at the very least, last several years and possibly your lifetime. Your input into the build process can be granular – depending on your knowledge, expertise, and inclination – or you can let the gunmaker lead. If you’ve picked your gunmaker wisely, either path will lead to your satisfaction.When Brown ordered his .410, he knew exactly what he wanted, and what he needed to provide to the gunmaker. He had his stock measurements sorted and had a blank squirrelled away since the 1970s which he provided to Westley Richards. He specified a barrel length of 28 inches fitted with Teague multi-chokes. ‘This was a gun to really use, not just to swing around in the parlour’.

He debated back and forth between the classic splinter forend, which he likes best, or a beavertail. ‘I knew 99 per cent of the shots were going to be on the skeet field, and sub-bores get hot very quickly, so a beavertail it would be’. Brown had a .410 Parker with a beavertail shape he liked, so he took measurements and photos and sent them on.

Brown had in mind for engraving small fine scroll surrounding game scenes (after illustrations in William Harnden Foster’s classic New England Grouse Shooting), with the fences ornamented with carved depictions of Eryngo, a thistle-like plant native to Texas. This was a personalised aesthetic signature that would make his gun unique. Initially, he hoped to have his old friend Geoffrey Casbard – whom he’d met through Walter Clode in 1969 – engrave it, but Casbard unfortunately passed away before the gun could reach him.

Instead, Clode arranged for David and Bradley Tallet to do the work. The results speak for themselves. ‘I’ve often thought that modern guns and their owners place far too much emphasis on engraving, sometimes at the expense of fit, finish and the lines of the gun itself’, Brown said. ‘However, when it came right down to it, I was as fixated on the engraving as all the others I’d been critical of’.

LET THE GUNMAKER LEAD

Not everyone has the benefit of a half-century’s experience with best guns, nor the time to learn the finer points of choosing wood and engraving. Your gunmaker will offer expert help as needed.

‘We often head up the project now especially with our highest-grade “Modèle de Luxe” and “Modèle de Grande Luxe” projects’, explained Managing Director Anthony Alborough-Tregear. ‘The client wants us to create a masterpiece for them. They want the very best of everything. Most clients need plenty of advice and guidance, we expect very little from them. If they let us run with it, the final product will exceed all their expectations’.

And this expertise isn’t all about aesthetics and ‘show’ guns. When Simon Clode was rebuilding Westley Richards, he cultivated a staff and a company culture imbued with a passion for shooting and hunting. Alborough-Tregear is cut from the same cloth: ‘Our guns and rifles actually get used, often in cases where a hunter’s life depends on reliability’, he said. ‘We understand the importance of balance, handling, pointability, reliability, and – in the case of rifles – accuracy’.

HERITAGE & HOUSE STYLE

Only a handful of British gunmakers have survived from the 19th century into the 21st with factories and unbroken histories, and each has its own ‘house style’ – distinctive aesthetics that have evolved over the centuries. Boss, Purdey, Holland & Holland, Westley Richards – the action shapes of one maker will be distinct from the others; so, too, gunstock shapes and proportions. The file-up of triggers, safeties, toplevers, trigger-guards will differ from brand to brand; sometimes subtly, sometimes very visibly. The blade of the One Trigger, for example, looks like no other – and its shape properly belongs only on a Westley Richards. Standard house engraving patterns have lasted because time has shown they complement the lines of each maker’s gun, and enhance the beauty. As the customer you have considerable latitude to create something unique, but keep in mind it will look best if it falls within the broad parameters of your gunmaker’s heritage. Respect that.

THE WAITING GAME

Had you wanted a new Westley Richards just before the First World War, you would have visited its London retail premises at 178 New Bond Street and there you would have been met by an expert staff and an inventory of hundreds of guns and rifles: up to forty different types of shotguns and eighty models of double rifles, not including ball-and-shot guns, magazine and single-shot rifles, revolvers and pistols, and the odd harpoon or sealing weapon. Each model of shotgun would have been available in a variety of grades and in different bores, with choices in barrel length, stock measurements and engraving patterns. If a configuration suited you, Westley Richards would have easily altered it to meet your gun-fit or choke requirements in a matter of days.

And a best-quality Westley Richards expressly ‘built to order’ might have been ready for you from the Birmingham factory in Bournbrook in as little as ten weeks – ‘during which time, it would have engaged the attention of fifty or more skilled craftsmen… and, in addition, that of expert cartridge loaders and shooters on the testing ground’, noted Managing Director Leslie B. Taylor in 1913.

Those days, regrettably, have passed. More than a century of contraction in the traditional gunmaking trade has shrivelled the ranks of craftsmen worldwide, apprentices are few and fought over, and completion times for new commissions are no longer two or three months, but two or three years. ‘Have patience’, counselled Alborough-Tregear. ‘A new gun or rifle is truly bespoke, and built by a small team of highly skilled individuals, each contributing to the finished article. If a single craftsman falls ill or goes absent, it can cause a knock-on effect, disrupting the team’s production process. There simply aren’t a dozen other guys out there who can do the job’.

And lavish engraving will probably not hasten delivery. One-of-a-kind projects take not only considerable more time to design and execute but capable engravers are often booked many years in advance, and have time slots scheduled for each commission.

‘A machine can assist with the manufacture of basic components, but a man puts his soul in to a gun’

If a gun doesn’t arrive for its intended slot – regardless of the reason – the engraver will need to rebook it in to his already tight and crowded schedule. There’s also an equal possibility that the maker delivers the gun on time but the engraver isn’t ready to take it. It will have to wait until he is. Such is the price of art.

If today’s client requires patience what then should job expect of his gunmaker? ‘Honesty throughout the build process’, answered Alborough-Tregear, ‘especially if the gunmaker is running behind. Communication with the client is important, and is welcome, but that doesn’t mean you have to contact him every week’.

Factory visits are encouraged. ‘We really enjoy visits’, said Alborough-Tregear. ‘It shows the client what we are really about. And it’s good for the gunmakers too; they feel appreciated and like to show off their skills and knowledge’.

‘The final product will be beautifully built, with real care and attention to all aspects, including any casing and tools’, said Alborough-Tregear. ‘Making a gun by hand is simply a slow process. Luckily for us, most of our clients understand that’.

MADE BY HAND

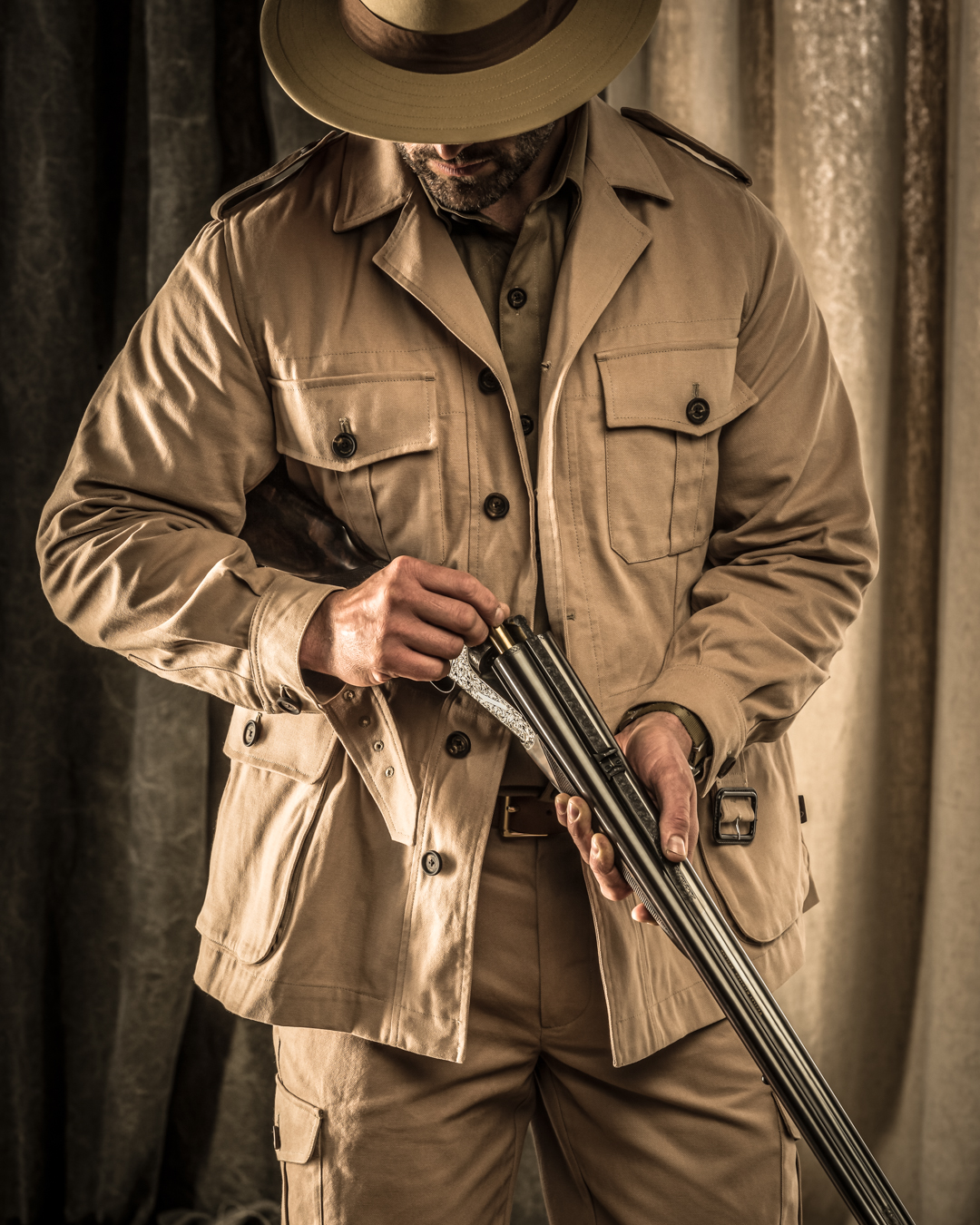

As noted, Westley Richards in the 19th and early 20th centuries sold ‘stock’ guns and rifles, as well as those ‘built for me’. Though guns in the latter category were expressly made to suit a client’s most rarified requirements, and were generally more expensive, both types were, as the company stressed, ‘handmade’.

As a period catalog stated: ‘Westley Richards guns are handmade throughout; no two guns are just alike, each gun has an individuality of its own, which can only be contributed by the bestowal of personal skill and trained craftsmanship’. More than anything it was this attribute that signified a British sporting gun’s prestige and worth and differentiated it from less-expensive continental and American competitors.

A century on, Westley Richards still steers this course. ‘A machine can assist with the manufacture of basic components, but a man puts his soul in to a gun’, said Alborough-Tregear. Two characteristics of ‘handmade’ are aesthetic beauty and handling. No machine-made gun has these qualities in the same way, as the machine isn’t capable of adding the human touch. Today it can work to microns, but it doesn’t appreciate the ‘feel’ of what it has made. With a hand-made gun, everything that goes in to building it – barreling, actioning, stocking, finishing – is carefully considered and individual skills are used to interpret each aspect. Collectively, this produces in real terms a truly unique piece – your gun or rifle will be like no-one else’s in the world.

And that’s the beauty of a gun built for you.

Whether for the discerning collector or the avid sportsman, Westley Richards firearms represent the epitome of excellence in the world of bespoke gunmaking. Known for the droplock shotgun, over and under shotgun, double barrel rifle and bolt action rifle, the company has achieved an illustrious 200 year history of innovation, craftmanship and artistry. As part of our best gun build, clients can choose from three levels of gun engraving: the house scroll; signature game scenes; and exhibition grade masterpieces. All Westley Richards sporting arms are built at their factory in Birmingham, England. Discover more about the gunmaking journey at our custom rifles and bespoke guns pages.

Enquire

Enquire