‘Every Ovundo, every gun, you look at here will be filed up slightly different.’

In the 3-1/2 decades preceding the 20th Century, breechloading—then hammerless—side-by-side guns were perfected in a wide variety of designs. The decades immediately following the turn of the century witnessed the introduction of seminal over/unders that remain influential to this day.

Innovation had sprung from all quarters in Britain but arguably most abundantly from gunmaker Westley Richards. Company literature of the time touted the firm’s “modern” approach to gunmaking and its “progressive spirit” and, in both cases, it wasn’t mere marketing hype.

Since its founding in Birmingham in 1812, Westley’s had pushed the boundaries of firearms technology, introducing notable improvements in percussion, breechloading and military gunmaking as well as in ammunition.

With their revolutionary patent of 1875, Westley’s William Anson and John Deeley had created the genesis for the modern sporting shotgun—a gun with concealed hammers as well as locks that cocked with the fall of the barrels. The firm’s doll’s-head top extension and bolting system were enormously influential, its mechanical single trigger and ejector systems proven, and its forend fasteners were (and still are) trade standards. Westley’s detachable locks—more commonly known in America today as “droplocks”—were nothing short of a stroke of genius.

Since 1895, Leslie B. Taylor, the latest in a long line of enterprising Westley leaders, had headed gunmaking operations. An innovative, bench-trained gunmaker with a scientific mind, he was described in 1912 by The Field as “a man of virile and energetic personality . . . [who] has kept the firm to the fore during an epoch when invention was proceeding at a rapid rate.” Unlike much of the Birmingham trade, which typically relied on a network of outworkers, Westley’s was mostly a self-contained operation with its own dedicated factory, and the firm took great pride in building guns to its own designs—guns made with every intention of competing with those of London.

And by 1910 or so Leslie Taylor would have realized Westley’s faced formidable competition from a new London design: the superb over/under of 1909 from Boss & Co.’s John Robertson, who had worked earlier in his career at Westley’s. With the side-by-side long perfected, over/unders gave makers of the day a new product in a sated market where sporting guns were increasingly difficult to differentiate.

The next five years produced a welter of additional over/under patents—among others from C. Lancaster, E. Green, W. Baker, F. Beesley and the inimitable 1913 design of J. Woodward.

Taylor’s response—the Ovundo—would incorporate many of Westley’s most famous patents and showcase a few new ones as well. In retrospect Westley’s over/under was the final flourish of a golden age of gunmaking at the firm—a precursor, in fact, to the modern Perazzi-type detachable-trigger gun. It became popular in the heady years just after World War I, before vanishing as World War II approached. And now, after more than a half-century absence, a revivified firm is making new Ovundos in an expansive new factory in Birmingham.

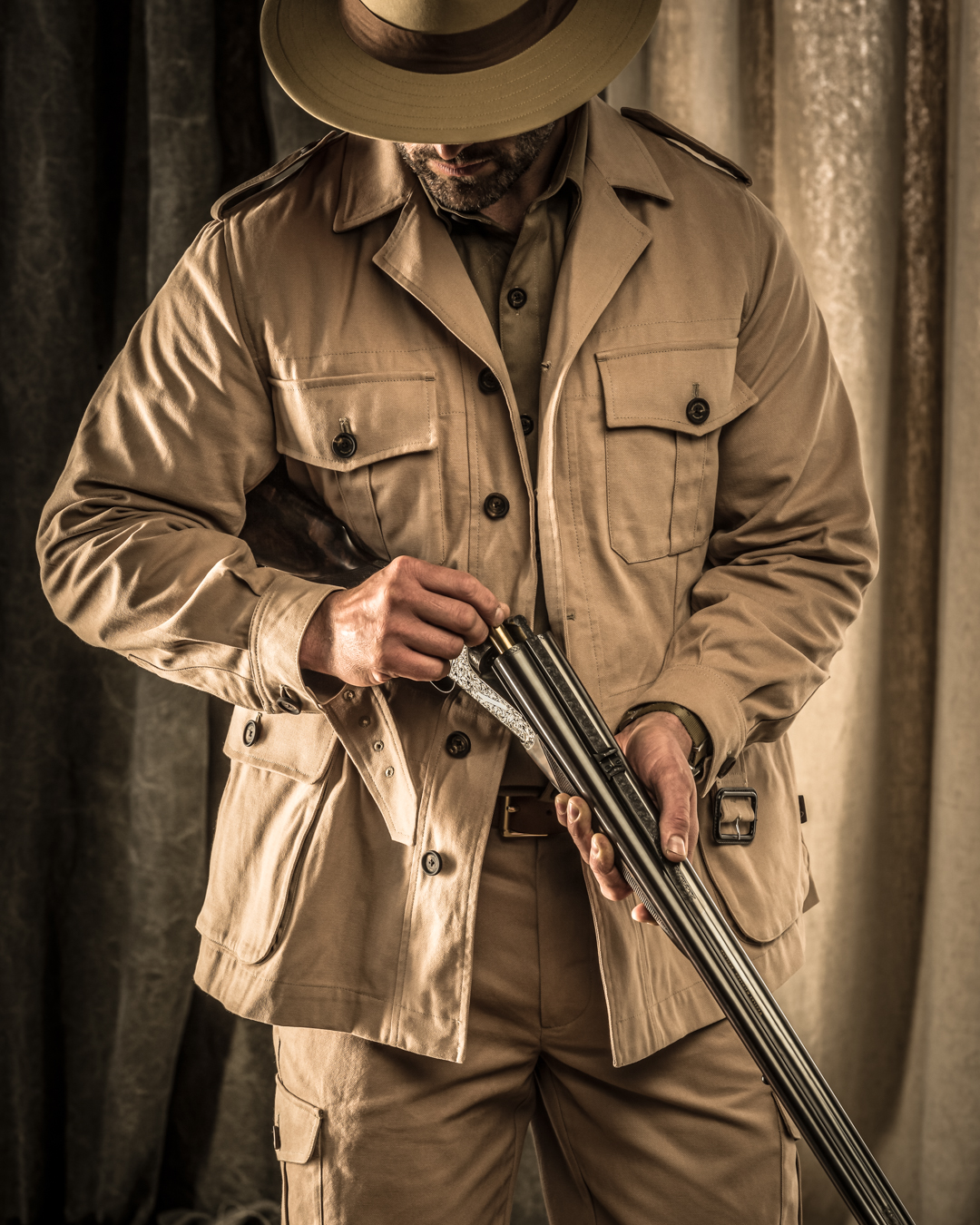

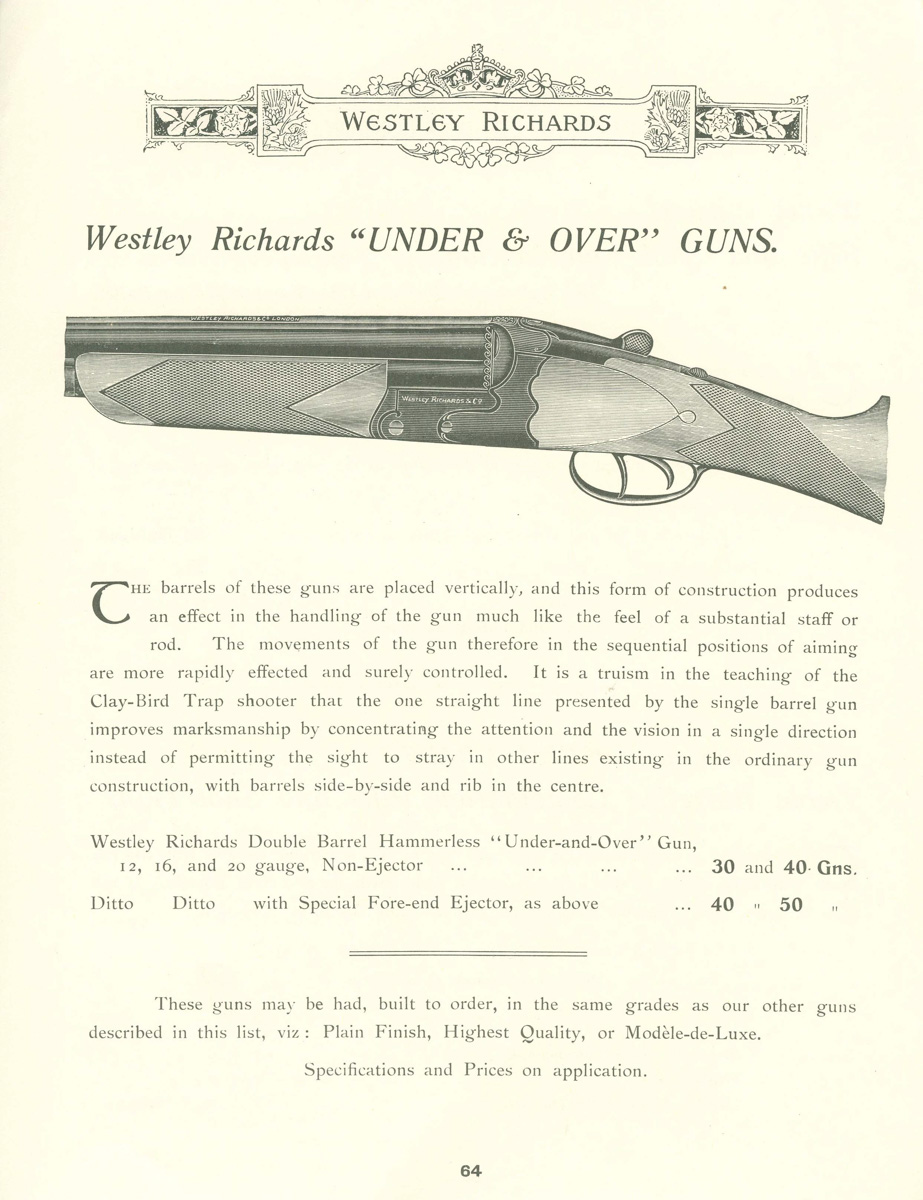

Westley’s initial entry into the growing O/U market had come in 1912 with a gun described in its 211-page Centenary catalog (see illustration above) as its Under & Over gun. In the fall of 2006 at the firm’s old factory in Bournbrook, I sat down with Simon Clode, Westley’s managing director, and Ken Halbert, then foreman of gunmaking operations, for an exclusive preview of the firm’s new Ovundo as well as to document the design’s history. (Halbert has since retired but still works part-time.) Neither had seen an example of an Under & Over, but if the sketchy catalog illustration is accurate, then it is possible it was a different design from the Ovundo, which would succeed it two years later. Just how different awaits detailed examination of an extant example, should one survive.

The Under & Over first appears in the Westley record books as gun No. 17431, made in 1912. It was advertised as being available in 12, 16 and 20 gauges and was priced from 30 to 40 guineas for a non-ejector version and 40 to 50 guineas for an ejector version—well below the 70 to 95 guineas charged by Westley’s for its “best”-grade hand-detachable side-by-sides.

Under & Over No. 17431 was possibly a prototype model, as the record books indicate it was never sold and its barrels were described as “waste” in 1930. The first gun to specifically bear the “Ovundo” name is listed as No. 17500, made in 1913. This gun was not sold until 1930, and it was likely another prototype. It appears that one Norman Goodenham placed the first legitimate Ovundo order in July 1914, for gun No. 17530.

While London’s makers concentrated on sidelock O/Us, Leslie Taylor and his gunmakers modeled their version on the house designs Westley’s had invented and made famous. Today we know little of the Ovundo’s actual development process; Henry Payne, a craftsmen who later would become Westley’s works manager during World War I, is known to have had a hand in its making along with Taylor, but to what extent is poorly documented. The record books, however, indicate that an individual named “Payne” actioned many of them.

In its most elemental form the Ovundo was a boxlock with either fixed or Taylor-patent hand-detachable locks with superposed barrels that hinged on a conventional hook located beneath the lower tube. What was novel and new was its barrel-bolting system (Taylor’s patent No. 4853 of 1914): two hooks, which extended from buttresses on either side of the barrels, fitted into slots in the face of the action. When the gun was closed, bolts actuated by the toplever rested atop the hooks and locked down the barrels. At the same time any forward motion of the barrels upon firing was prevented by the bearing surfaces of the hooks contacting corresponding bearing surfaces in the slots in the action face.

The Ovundo was unique in that it was entirely of Westley Richards design: In addition to its locks and Taylor’s bolting system, its toplever, top safety bolt, ejectors, hinged cover plate and mechanical One Trigger single trigger were in-house inventions. Moreover the gun showcased a new patented hinged trapdoor on the sideplates that allowed access for lubricating the selective Westley One Trigger (a mechanical marvel in its own right and one of the truly great British single triggers).

Unfortunately, the Ovundo could not have been introduced at a worse time; the guns of summer 1914 did not sound on the grouse moors of Scotland but across bloody fields in France and Belgium. For the next four years sporting-gun production essentially ceased as Westley’s concentrated on war work.

Westley’s left the war years behind on better legs than many of its notable Birmingham competitors. For one, Leslie Taylor was still at the helm. Under his expert leadership, the company was in a position to tap a burgeoning American market and, most importantly, the patronage of fabulously wealthy Indian princes. Ovundo production restarted in 1919.

According to Ken Halbert there were four major Ovundo variants: a fixed-lock gun with a scalloped (or rebated) action back, a fixed-lock version with sideplates, a detachable-lock version with a scalloped back, and the detachable-lock version with sideplates—the latter being the best-known and most-expensive variant. Another variant of the fixed-lock non-sideplated model was a version with a flat (straight) action back instead of scalloping. These were sold as Special Model Ovundos and marketed as “trap and field” guns. The Ovundo was available with single or double triggers, and Halbert says that single-trigger guns are most common and that sideplated versions might or might not have the hinged trapdoor on them.

Unlike Boss or Woodward O/Us, which invariably were built as best guns (with best-gun prices), the Ovundo was available from mid-grade to best-grade, a deliberate attempt to bring the British O/U to a broader range of potential consumers. It was advertised in 12, 16 and 20 bore—“or smaller bores,” although it appears that only one 28-bore was made. In 1925 the non-sideplated Special Model started at £65, whereas the Highest Quality best sideplated gun with all the bells & whistles commanded £150. (A best Woodward O/U also sold for £150 at the time, and a best Purdey side-by-side was approximately £130.)

Archival research conducted by Westley’s Gun Room Manager Anthony Alborough-Tregear indicates that most Ovundos feature the more-expensive droplocks. “Only the first few were fixed locks,” Tregear said. “Then over 90 percent were detachable locks. It seems when people ordered our over/under they wanted the detachable lock.”

The Ovundo was also fully capable of being built in double-rifle configurations, from .22 HP to .425 bore, with the company’s .318 Westley Richards being its most popular chambering. The gun also was made in Westley’s proprietary rifled-choke ball & shot configurations as the 12-bore Explora or the 20-bore Fauneta.

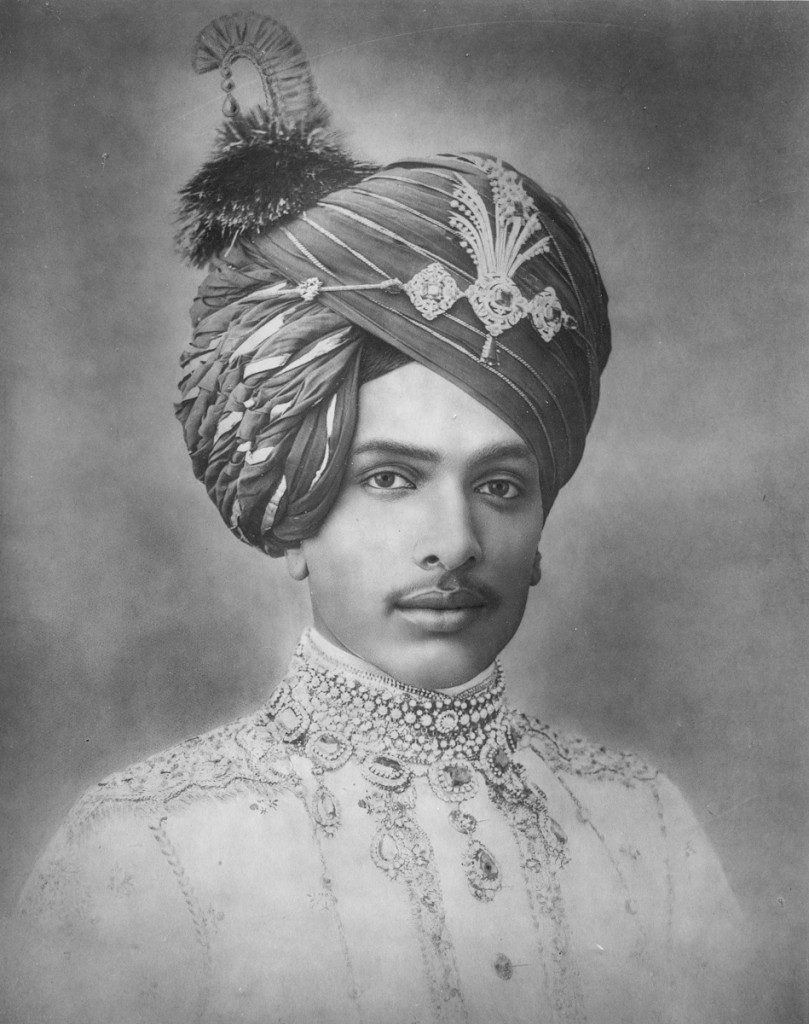

Two of Alwar's Westley Richards Ovundo rifles top in .350 and below .240.

Two of Alwar's Westley Richards Ovundo rifles top in .350 and below .240.

By the mid-’20s Westley’s was promoting the Ovundo as its “modern masterpiece” and “the perfect modern gun.” Americans (among others) were becoming increasingly fond of the over/under configuration, especially for live-bird competitions and the growing sport of clay shooting. The records show a sizeable number of Ovundos being shipped to one Bob Smith, evidently an importer in Boston. A good number of these were non-ejector guns. Also at that time company literature touted Belgium’s Henry Quersin, editor of Chasse et Peche, as winning several clay- and pigeon-shooting championships with his Ovundo. The Indian princes were particularly partial to Ovundos in double-rifle configuration as well as in the Explora and Fauneta versions. The Maharaja of Alwar, for example, ordered 10 Ovundos between June 1922 and December 1925—one in .240, one in .318 WR, six in .350, and a pair of Fauneta 20-bores. An examination of record books makes it clear that the Ovundo was at its pinnacle of popularity in the Roaring ’20s. The ’30s, on the other hand, ushered in tougher times. Not only had the Great Depression descended, but Leslie Taylor died in 1930 and Henry Payne was killed in a tram accident in ’33, talent sorely missed in coming years. As the decade wore on, Ovundo production tapered off; by 1938 the gun essentially had ceased to be made on a regular basis. A few scattered references to Ovundos continue to pop up at later dates in the archives, but most appear to be either rebarreling jobs or guns finished from orders or actions started years earlier. Judging by the main record books, it appears thatmore than 200 Ovundos of all configurations were produced.

The Maharajah of Alwar who was the owner of many of the initial Ovundo guns and rifles.

The Maharajah of Alwar who was the owner of many of the initial Ovundo guns and rifles.

That makes the Ovundo one of the more successful British over/unders of its era—even if its era was short-lived and its long-term influence not as pervasive as those of Boss and Woodward O/Us. Like any vintage British O/U, the Ovundo was a challenging, expensive gun to build, especially in its detachable-lock versions, and it was ill suited to the world’s desiccatedeconomies of the Depression.

The demise of the Ovundo also was indicative of the declining health of the company. World War II wrecked a tottering British Empire and so too the firm that depended on it. Capt. E.D. Barclay purchased the bankrupt business from liquidators in 1946, and Westley’s muddled through another decade before being sold to Capt. Walter Clode in 1957. Clode kept Westley’s gunmaking going through some lean years—largely through repairs and renovations to second-hand guns that he was buying from the armories of Indian princes—but he also concentrated on modernizing the firm’s high-tech engineering and toolmaking operations. It was a move that would pay great dividends when his son, Simon, joined the firm in 1987.

Simon set about integrating the CNC millers, spark-eroders and wire cutters of Westley’s engineering division with the files and chisels of the firm’s bench-trained craftsmen. At the time, the gun Westley’s was best known for—its great hand-detachable-lock side-by-side—was still being made in 12 gauge, but it was being made sporadically and by hand and virtually on a one-off basis, making it very costly and inefficient to produce.

Simon’s goal was to bring the detachable-lock gun back into regular production using the latest manufacturing technology married to traditional gunmaking skills. In the late 1980s he launched this process with the .410 version, only six of which had ever been made. Initially, 10 were produced to great success, and since then Westley’s has followed up with 28-, 16-, 20-, 12- and 10-bores, as well as rifles in a host of calibers. Even an 8-bore is currently under construction. Significantly, all are built on scaled frames appropriate to each gauge or caliber.

With the hand-detachable back as its core product in shotgun and rifle, Westley now also makes bolt rifles and sidelock shotguns and rifles as well as its own proprietary rifle ammunition. Under Clode’s direction the company also has diversified into making its own best-quality gun cases and leather goods. Virtually everything, save the ammunition, is made in-house. In 1997 the firm opened a US agency to better market its goods and guns to the American market.

As Westley’s nears the end of its second century of continuous operation, Clode has invested massively in the company’s future. This past May the firm moved from its historic Bournbrook factory to a new 4-1/2-acre complex near the heart of Birmingham’s old gun quarter. (The Bournbrook facility, dating to the late 1890s, is being leveled to make way for a new road.) Located in what was an old enameling factory, the 20,000-square-foot building has been fully refurbished. “The first floor is all gunmakers,” said Tregear, who returned to Westley’s in April after a stint with E.J. Churchill. “It has separate rooms for all aspects of gunmaking—actioning, finishing, stocking and engraving. On the same floor but in an adjoined part of the building is our leather-goods division. We also have a proper retail store that offers the best brands of shooting clothing and equipment.” Westley’s engineering division, which designs and manufactures press tools for automotive and general industries, also has moved into a new 20,000-square-foot facility next door.

“We are the place to find everything under one roof,” Treager said. “From shooting clothes and equipment to pre-owned and bespoke guns to shooting trips around the world—we do it all. We are English-owned, and we are investing in the future of English gunmaking like no one else in this country.”

Clode’s vision and Westley’s unique guns—and the quality with which they are made—have garnered Clode a loyal and discerning clientele base as impressive as any since the halcyon days of the Empire. Among them number not only the bulk of the world’s most prominent collectors but also kings and princes from across the globe. It was largely his customers’ interest in a new Westley O/U, according to Clode, that led to the Ovundo’s reintroduction. “The new Ovundo has been a long time in the making,” Clode said. “We needed to get our side-by-side shotguns and double rifles going first.

“From the outset, I had no intention of introducing a modern competition-type O/U into the market. The Ovundo was historically our gun, a traditional English gun, and we decided to build it on that basis.”

The first pair of Westley Richards 20g Ovundo's.

The first pair of Westley Richards 20g Ovundo's.

In Clode’s office in the old factory I had a look at the first new Ovundos completed—a matched pair of sideplated 20-bores engraved by Alan Portsmouth with birds of prey and Westley’s bold scroll. Built for a modern-day King Croesus in the Middle East, they were impeccably made and, at 6 pounds 4 ounces each, as lively and well balanced as any best British side-by-side. Compared to a Boss, the Ovundo has a tall action but is by no means ungraceful—particularly in 20 bore—and in the hand it handles superbly. My only regret is that I did not get to shoot the royal pair.

New Ovundos currently are available in 20 and 16 bore on scaled frames, and a rifle version in .318 is under consideration. The configuration is Westley’s Highest Quality version: hand-detachable locks, sideplates with trapdoors, the 1909-patent selective single trigger, a Deeley forend latch and an ebony forend cap. A best-quality Westley Richards through and through. Double triggers are an option, as are a number of top-rib configurations. Prices start at £43,500.

Mechanically, the new Ovundo remains largely faithful to its predecessor. Apart from making a lock-locating stud integral with each lockplate (rather than drilling it in the action), little was done to improve the original design. “The Ovundo hasn’t changed, really,” Halbert said.

There were no craftsmen left at the factory who had helped build the original Ovundos, so Clode and Halbert appointed actioner Henri Laurent, a 30-year-old French-born gunmaker, to head up the project. Laurent—a graduate of the Liège School of Gunmaking who’s served time at Holland & Holland and E.J. Churchill—had the task of discerning any problems in development, coordinating between the engineering and gunmaking departments, and creating a manufacturing procedure. “To graduate in Liège, you have to be able to build an entire gun,” Clode said. “Henri is very good and, with his broad range of skills, he was the right man for the job.”

The fact that the Ovundo is back and that there are young men like Laurent (among others) making them speaks volumes about the current state of affairs at a firm that is only five years short of being two centuries old.

Fifteen craftsmen, young and old, work at benches in the manner their predecessors did a century ago. Modern engineering has indeed been integrated into the gunmaking process, but Clode has deliberately restrained it from supplanting traditional craft. “Our machinery could make a new gun to near-finished specs,” Clode said, “but then you quickly lose traditional gunmaking skills. Once those skills are gone, they are gone for good.

“Every Ovundo, every gun, you look at here will be filed up slightly different, and if someone makes a tiny surface error filing it, it has to be blended in. That’s part of the beauty of a hand-crafted gun.”

Much has changed in gunmaking—and at Westley’s—since Leslie Taylor showcased the first Ovundo. Almost a century on, Simon Clode is not content to rest on the laurels of his predecessors but is more interested in preserving the time-honored skills that created them in the first place. Founder William Westley Richards had a simple motto: “To make as good a gun as can be made.”

The Ovundo is new again, but Westley’s motto has remained the same.

Vic Venters is Shooting Sportsman’s Senior Editor and this article has been reproduced with his kind permission.

This article first appeared in Shooting Sportsman magazine some 5 years ago. Our order book for the Ovundo is in fact now closed and we are no longer taking further orders, please see previous post.

Enquire

Enquire