There has always been a degree of reluctance among shooting men to allow their gun-maker to deviate from what they quite arbitrarily consider his ‘true path’. History is littered with the failed campaigns of those who have tried.

For some reason, we Brits have it hard-wired that we want to buy our boots from a boot maker, our hats from a milliner and our guns from a gun-maker. The upper echelons of society were once so demanding that they were used to seeking a dedicated specialist provider of everything from shaving brushes, to hunting coats, to corsets. Every one a master of his art or craft.

The Hunstman

The HunstmanThe notion of a generalist or department store emerged in the mid-Victorian era and was an undoubted convenience but somewhat less satisfactory than having ‘your man’ in a specialist position providing your most important essentials and luxuries. Patrons of gun-makers often had long and involved relationships with the establishments they favoured. Think of Lord Bentinck and James Purdey or Col. Hawker and Joseph Manton, as examples.

As commerce became more widely transactional and the middle classes joined the aristocracy as consumers of fine goods and services, the temptation to expand into potentially lucrative side-lines must have occurred (actually did occur) to many in the gun trade.

However, even mild deviation from the expected could prove detrimental to the core business. When Purdey began selling lower grade guns, discretely marked ‘B’, ‘C’ or ‘’D’ Grade, mostly finished in London from barreled-actions sourced and then partly made-up in Birmingham, the word soon began to travel that Purdey was now selling ‘Birmingham guns’ and it would be as well to go to William Evans who did the same thing but charged a good deal less.

By tapping into the ‘less than best’ market, Purdey hurt their reputation for first-class work, which remained the vast bulk of their trade. As a result, the lesser quality grades were quietly dropped and Purdey went back to best quality only. Boss went a step further, making the slogan ‘makers of best guns only’ a distinct byline for the business.

The Countryman

The CountrymanFor businesses that focused on an exclusive clientele and sold them ‘the best’ at a high cost, the customer wanted it explicitly clear that if he was holding a gun by the firm he favoured, nobody could be in any doubt that it was the best that could be made and was sold at a price point only available to the very well-heeled.

Some gunmakers sold in volume and, while capable of the very best work, also sold many other grades of gun and rifle, often making them for the trade as well as for sale under their own name.

W&C Scott is a good example, as is Bentley & Playfair. Their best quality guns were often sold with the names of others on the lock and rib, while they also provided medium and lower quality guns to other echelons of the gun trade, be they London ‘makers’, provincial gun shops or even small town ironmongers.

The Sportsman

The SportsmanStill, the allure of expanding into the peripheral accoutrements of sport continued and many successful firms became involved in building inventories of everything a sportsman might need for his shooting at home or an expedition abroad. In time, the notion of the gun-maker acting as an outfitter became more prevalen.

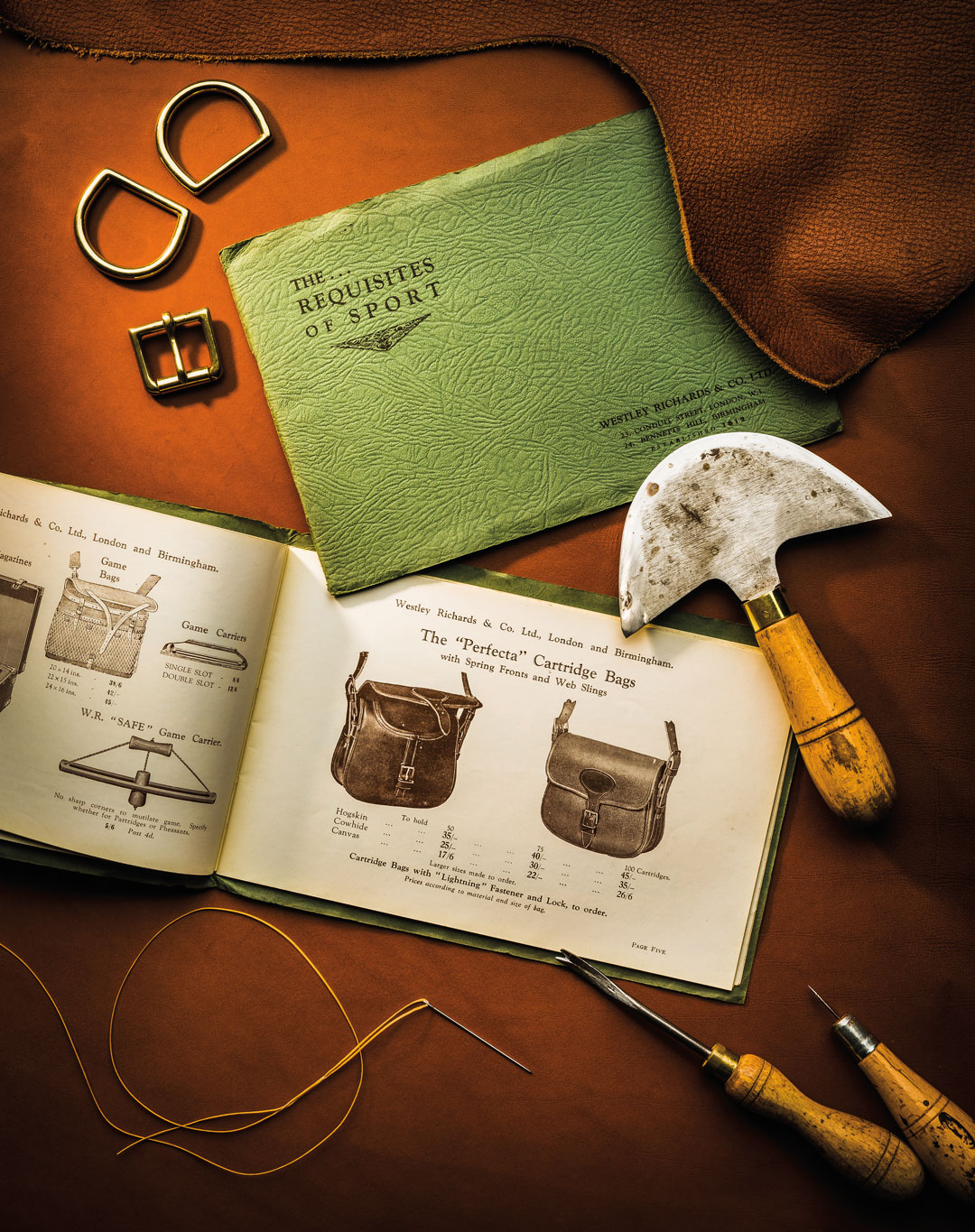

Westley Richards published a small booklet in the early 1900s called ‘The Requisites of Sport’. It contained, as may be imagined, a wide range of accessories and clothing that would appeal to the shooting man of the day.

Among the contents can be found ‘The Hurricane Lightweight Waterproofs’, gun cabinets, clay pigeon traps, hunting canteens, holster flasks, gun cleaning fluid, cartridge bags and dog whistles.

Richard Beaumont wrote about the beginnings of Purdey’s clothing line, started by his wife and rapidly growing to become a significant part of the income of the company, as it still is today.

Chris Hunter was, for many years the man behind the Purdey clothing lines. During his tenure, Purdey clothing was always of superb quality, in distinctive tweeds, and cut so that it was as comfortable on the peg swinging onto a partridge as it was on the London underground travelling to a rugby match.

Chris went on to establish William & Son as perhaps the best quality and value outfitter in the West End for sporting clothes and accessories.

Holland & Holland had, what appeared to me to be, a cyclical and somewhat schitzophrenic relationship with their clothing lines. In the early 2000s it was probably the best in class. They then brought in a designer to re-focus it as a high-fashion brand, with safari and shooting-field themed designer outfits that, frankly, were unfit for serious out-door wear. That failed and there was a volte-face returning the lines to properly-constructed, beautiful quality shooting and safari clothing. Eye-wateringly expensive but unquestionably fit for purpose.

The Townsman

The TownsmanIn the years before selling to Beretta the clothing returned to the high-fashion, impractical format that had failed fifteen years earlier. Now owned by Beretta, in time I’m sure Holland & Holland will re-think their clothing and outfitting policies. Beretta’s own clothing is actually well-targeted to their clientele and very well done.

We, the public, have come to expect the shops operated by our great gunmakers to also sell branded and selected products; from whisky decanters to cigar cutters, cartridge magazines to i-Pad sleeves.

What is it that makes a customer choose his gun-maker as the source of his hat or belt? It has to be confidence that the goods sold are commensurate in style, quality, design-integrity and workmanship that he has come to appreciate in the guns. In short, the other goods are sold on the reputation of the core product. The association with a best gun and best gun-making confers brand value to other, related products.

This modern phenomenon is not unique to gun-makers, just visit any motor vehicle showroom and see the watches, jackets and hats co-branded with the cars or motor-cycles.

However, the age-old conundrum lies in wait for the unwary individual charged with stocking the shop. Only for as long as the products sold alongside the guns retain the quality and integrity the guns themselves possess will they co-exist benignly. Get it wrong and they will erode the reputation of the entire operation and degrade the brand value.

As a case study, Westley Richards proves interesting, as a long-established business using its core product of hand-built best guns and rifles to launch other goods of interest to not only existing customers but others who may be either aspirational or simply appreciative of what marketers now refer to as the ‘Brand DNA’.

This should be relatively straightforward when selling directly applicable sporting accessories and clothing. A cartridge bag, shooting suit or hat must be as fit for purpose as the guns themselves, made of the equivalent materials and cut so as to be stylish and practical when worn or used in the shooting field. It gets more complicated when extended into casual or formal apparel.

The Outdoorsman

The OutdoorsmanA customer buying a Westley Richards branded casual overcoat may not be a shooting man nor expect to drag his new coat over a peat bog in pursuit of a stag but he appreciates that a garment from the company will have design, construction and material integrity; things he values and, he believes, send out signals that he is a connoisseur of such things. The image it provides suits his sense of self.

It is not always practical, desirable or necessary to brand everything with the company logo. Sometimes outfitting means selecting the best items in their class from other makers and representing them to your customers, saving them the trouble of working out what the best of each item they may need is and where it may be sourced. This too is not a new phenomenon; many gun shops once sold accessories by Hawksley, leather goods and cases by Brady and oils by Parker Hale alongside their guns and rifles.

Today, Westley Richards sells not only its own-branded clothing and leather goods, but selected brands from around the globe, each one representing the best of its type, be that hats by Hutmacher Zapf, loden hunting coats by Hapsburg or field shirts by Filson. Each is an iconic brand representing its own specialist niche.

According to Stephen Humphries, the man leading the company’s creative direction and whose team populate the beautiful Westley Richards flagship showroom in Birmingham with appropriately classy items to tempt both the man collecting his one-hundred-thousand-pound rifle and the casually visiting premiership footballer, the essence of the project is to represent the best example available anywhere of every item in stock.

As an ever more challenging retail environment stresses long-established businesses, in the gun trade, as everywhere, those who adapt best will survive the challenges and thrive when conditions are favourable.

For the public to appreciate the wider retail experience surrounding the core business of best gun making, people have to retain respect for the core product. Without that, the house is built on a foundation of sand.

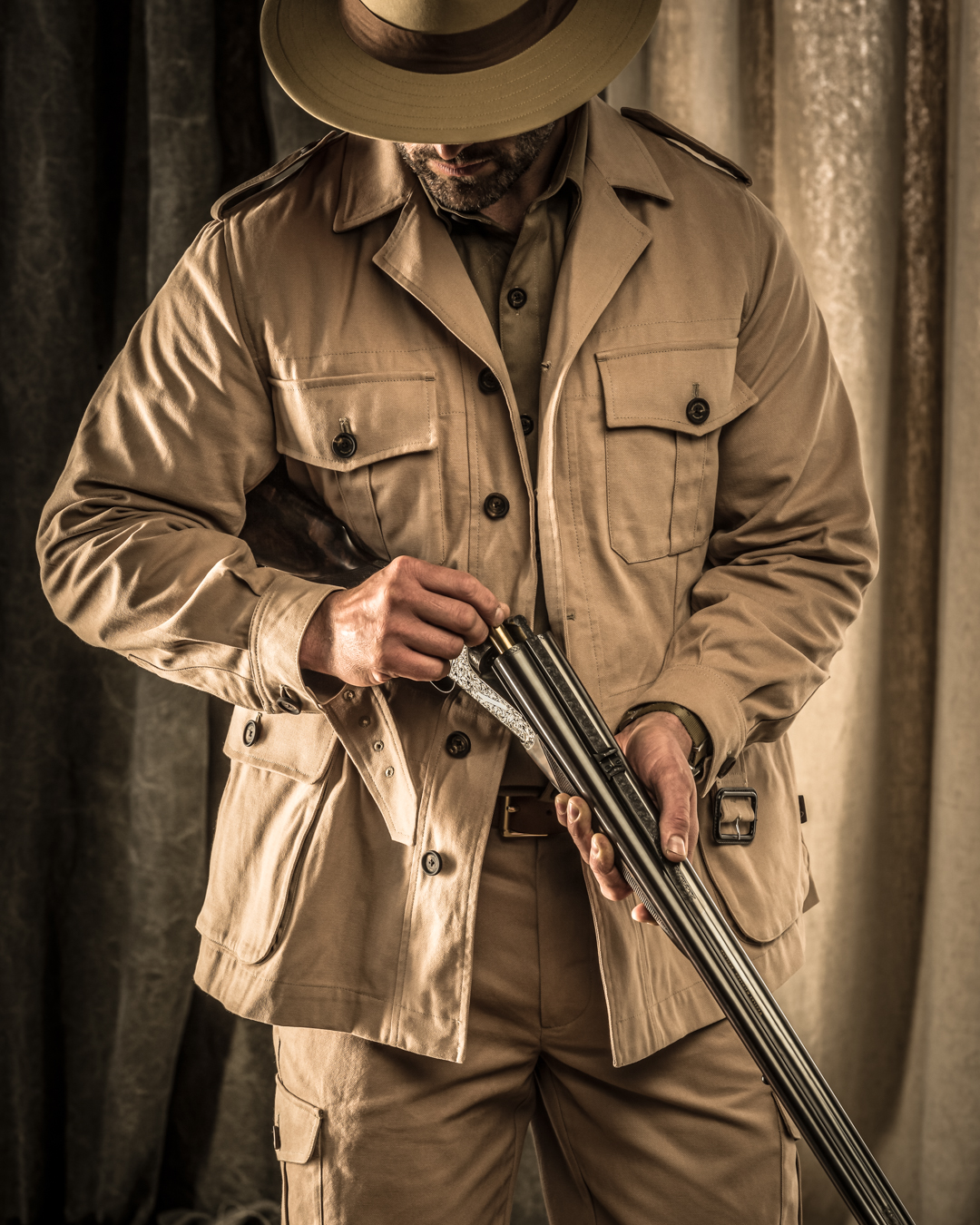

Alongside its custom rifles, luxury travel bags and high quality country clothing, the modern Westley Richards continues a 200-year tradition of outfitting hunters and adventurers for the rigours of outdoor life. With an unrivalled heritage of safari wear, the company produces a range of luxury safari clothes for the ultimate safari packing list. Inspired by former clients Ernest Hemingway and Stewart Granger each safari jacket, hunting shirt and cargo trouser reflects Westley Richards ethos of timeless style and exceptional quality. Pair a rugged safari shirt and safari shorts with some world famous Courteney boots and a classic safari hat.

Enquire

Enquire