When we look at the records of the British Patent office we find that between the years 1855 and 1872 alone he obtained no less than 17 major patents relating to firearms and many of these protected more than one invention. One of them No 633 of 1858 related to the design of the famous capping breech loader affectionately known as the “Monkey Tail”.

A CURIOUS TWIST TO THE MONKEY TAIL’S TALE

(Monkey Tail Variations)

By Brian C. Knapp

The Birmingham firm of Westley Richards is one well known to all with an interest in arms: a firm established in 1812 by William Westley Richards, surviving the passage of time and is still with us today.

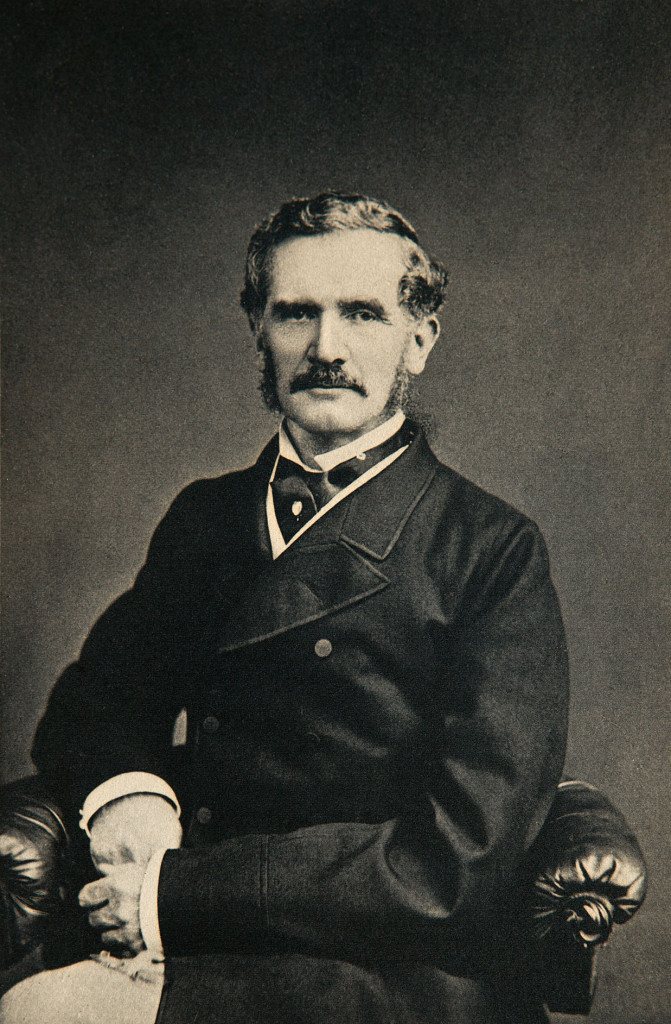

A capping breech loader is one of those transitional breech loading systems developed in the mid-nineteenth century, it is a gun loaded at the breech but fired by means of a percussion cap placed on an external nipple. It is one of the stages that firearms design passed through before development of the metallic self-contained center-fire cartridge.

The Monkey Tail is an arm that I am sure needs no introduction to readers of our list, an arm well know and sought after by collectors worldwide. It was without doubt the most successful of all British made capping breech loaders. The British War Office was to adopt it for cavalry issue and purchased over 2000 carbines direct from the inventor, a further 19,000 were made at the Royal Small Arms Factory Enfield under licence. Substantial numbers of rifles were also obtained for infantry troop trials, and further experiments were carried out with Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles converted to breech loading by this system. The military authorities of the day seriously considered adopting it as the first standard issue breech loading rifle of the army. Curiously this honour was given to the Mont Storm another capping breech loader in 1865, and then being passed to the Snider, when it was found the Mont Storm skin cartridges were to fragile to be practical for military use.

A testament to the success of the Monkey Tail in government service is the fact that it was not declared obsolete until 1881. An advertisement circulated by Westley Richards in the late 1860’s lists the following governments and units which purchased and used arms of this design.

One of the 19,000 Monkey Tail carbines Made at R.S.A.F. Enfield. Many were issued to Yeomanry Regts.

One of the carbines supplied to The Colonial Government of Victoria and issued the Victorian Volunteers, it is believed at least 600 were acquired.

A Portuguese contract Monkey Tail Rifle, 8000 were supplied by W. Richards in 1867.

Even after 1870 when the metallic cartridge breech loader was well established and proven, substantial numbers of Monkey Tails were still being manufactured and sold. Production continued into the 1880’s a date by which most other capping breechloaders had been consigned to the dustbin of history. The greatest demand came from the Boers in South Africa; for them it was an ideal and practical weapon, at the time even more practical than a metallic cartridge gun. Most of the Boers were poor farmers living in outlying districts; metallic cartridges could be hard to come by and expensive, yet most trading post would have a supply of powder, caps and lead. The Monkey Tail, used a paper combustible cartridge with a felt wad in the base to seal the breech on firing, although these cartridges could be bought, many owners preferred to make their own with a few simple tools that could be supplied with the gun. A further advantage was that the gun could also be used as a muzzle loader when no ready-made ammunition was available, an ideal weapon for the hardy veldt Boears whose survival could depend on a reliable and practical rifle.

The pattern of Monkey Tail favoured by the Boers.

It was to be this weapon that the Boers turned on the British in the first Boer War of 1881, and to great effect, the majority of the 500 Boers who defeated 647 British soldiers armed with the Martini Henry at Majuba carried the Monkey Tail. By European standards an obsolete weapon. The model favoured by the Boers was a short rifle version with a 24” barrel, easy to handle on horseback, yet slightly longer than the standard cavalry carbine, allowing extra-long range accuracy. It is said that Boer boys learned to shoot at an early age and were not considered proficient until they could hit a hen’s egg at a 100 yds. with a Monkey Tail rifle.

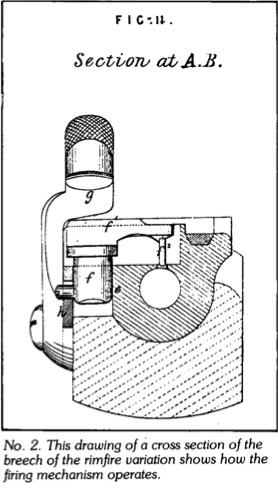

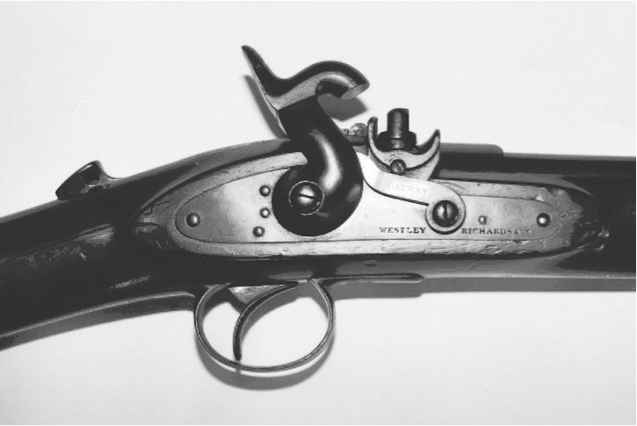

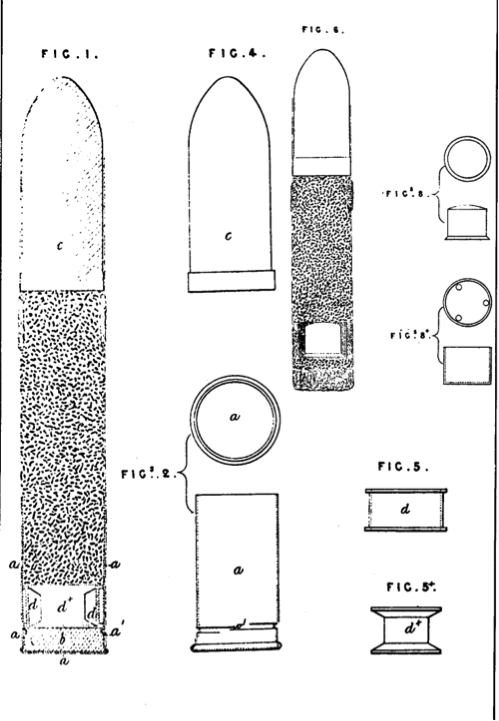

Returning to the patent records we discover that there are six patents relating to improvements, these take the basic design of the Monkey Tail from a capping breech-loader to a hammerless center-fire rifle using a solid drawn brass case. The first of these patents, No 2633 of 22nd October 1864, describes a rimfire variation and an unusual if not unique form of rimfire cartridge. It also details how existing arms could be converted to handle the new form of cartridge. The patent describes two variations of cartridge both being very similar, the first is detailed as a paper cartridge with a copper capsule base, which according to the patent was packed for a short distance with pulp or saturated felt. This is needed to ensure a gas tight seal and prevent blowback. The base was fitted with a disc of larger diameter, to prevent the cartridge being pushed to far forward into the chamber, and to assist its withdrawal. Just forward of the base was a double copper ring one fitting over the other, the inner one grooved and the groove filled with fulminate. A hard wood plug was placed in the centre of the brass rings to reinforce them and act as an anvil against the blow of the firing pin. The design and manufacture of this cartridge is best understood with reference to the illustration.

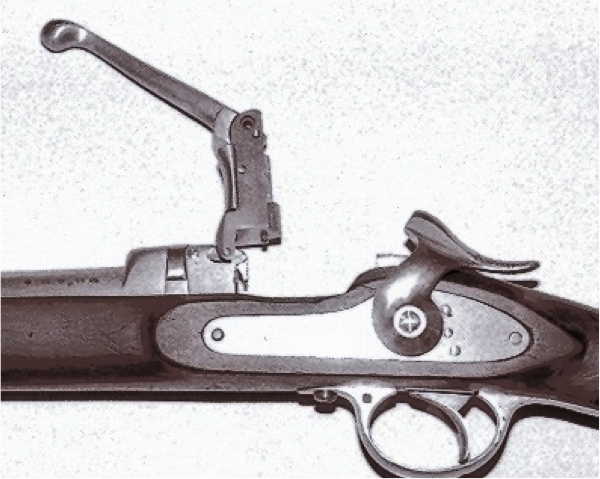

The second cartridge described is basically a variation of the first, the difference being that it did not need to be extracted after firing, but the remains fired out by the next round similar to the original capping breech loader. In this instance there was no copper base capsule, but attached to the paper cartridge case a felt wad (similar to the type used with the  Monkey Tail). Into this case was placed a brass fulminate ring as previously described only the centre being filled with hard rammed gunpowder instead of the wooden plug, which would burn up and leave nothing but the ring itself. The rifle to use these cartridges was designed somewhat differently to the standard model which we are familiar with. Existing examples followed the design of the common commercial 24” barreled short rifle; the patent describes the modified arm as having the nipple bolster bored with a vertical hole in place of the common nipple, its purpose being to act as a guide for a cylindrical plug. The plug was fitted with an arm at its top at at its end a firing pin which enters the chamber via a hole it the top to strike the cartridge rim. There was a mechanical means of returning to striker to the upright position.

Monkey Tail). Into this case was placed a brass fulminate ring as previously described only the centre being filled with hard rammed gunpowder instead of the wooden plug, which would burn up and leave nothing but the ring itself. The rifle to use these cartridges was designed somewhat differently to the standard model which we are familiar with. Existing examples followed the design of the common commercial 24” barreled short rifle; the patent describes the modified arm as having the nipple bolster bored with a vertical hole in place of the common nipple, its purpose being to act as a guide for a cylindrical plug. The plug was fitted with an arm at its top at at its end a firing pin which enters the chamber via a hole it the top to strike the cartridge rim. There was a mechanical means of returning to striker to the upright position.

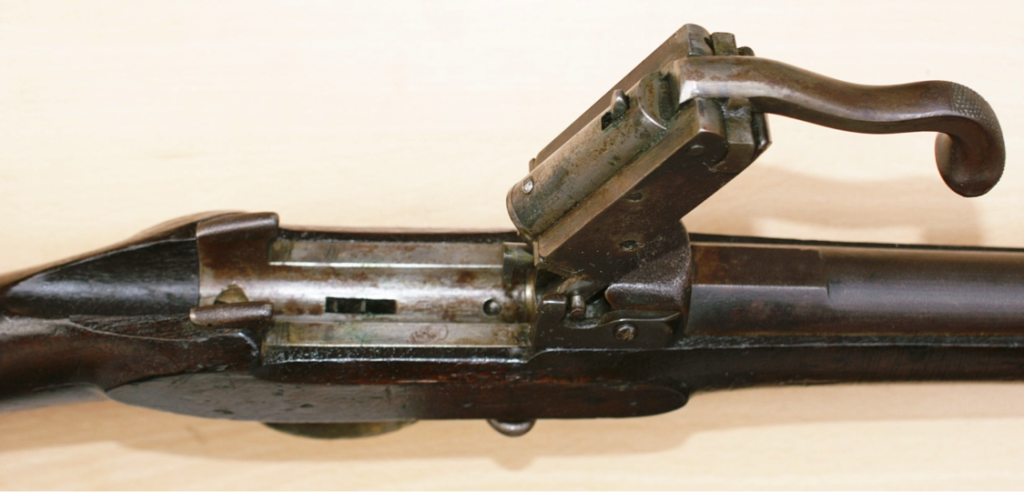

Top of Action Rimfire Monkey Tail.

Top of Action Rimfire Monkey Tail.

Arms made to this design are exceedingly rare and in all probability few were made. In reality it was complicated and offered and offered little advantage over the standard capping breech loading carbine. There is no doubt that it was an arm to this design that Westley Richards described to the Ordnance Select Committee in a letter dated 8th March 1865, The O.S.C. was an official body set up to examine and test arms and equipment for the British military. W. Richards had worked closely with this committee during the trials and subsequent adoption of the Monkey Tail into military service.

The committee in their reply expressed the opinion that they saw no reason to recommend this new system as a replacement cavalry arm. Only as in comparison with others submitted to the trials then being held to select a suitable breech loader for the infantry. Yet a year later the OSC realized that with the adoption of the Snider and improvements in metallic cartridges the 19,000 Monket Tail carbines then being manufactured at Enfield were already quit out dated. In August 1866 they contacted Westley Richards to request details of the system he had developed in adapting his carbine to handle cartridges containing their own mean of ignition. For reseason now lost in the mists of time, he refused and in no uncertain terms, his refusal was to serve him ill, for on examination of the OSC records for 1867, we find he was again in touch with the committee regarding a conversion system. Apparently he had developed a means of converting the service carbine to handle primed cartridges. The conversion could be carried out for a £1 per arm and special ammunition would be required, which he also described. His offer was turned down on the grounds that it was inadvisable to have two kinds of ammunition in the service.

The exact system he had in mind is not known, but the answer must lie in one of his patents of 1866 he obtained three in that year relating to improvements on the Monkey Tail system. The first of these No 688 which we shall examine next, describes a means of modifying the basic system to handle centre-fire cartridges. In this case the hinged breech block carries a firing pin, which runs through it at an inclined angle. The breech box into which this block fitted was not of the enclosed type, but had the sides cut away, allowing freer use of fingers during loading and unloading, a feature of all subsequent cartridge Monkey Tail’s. An extraction device is described as well as a number of different cartridges that could be used with the arm. It was fired by the standard lock and hammer, return of the striker was carried out by the use of the ordinary bent or sear spring. W. Richards thought this superior to the coiled spring.

Patent No 1960 of July 1866 is indeed quite interesting being the first to deviate from the original specifications to a greater extent. It describes an arm with a two piece breech block, the block forming one part and the lever the other. The block was hinged to a bracket fitted over the breech end of the barrel, this allowed the block to be pulled back a small amount, thus providing the action necessary for extraction.

At the rear end of this block was a hinged semi-circular wedge piece, which also formed part of the lever. The principle being that when the breech was closed, the act of pulling the lever down in a circular motion would turn the semi-circular wedge piece into matching machined form in the fixed breech locking it solid. The striker mechanism described in this patent has been modified from that in 688, in this case the striker runs parallel through the block, fitted to the rear of the striker is a projecting piece that protrudes through the side of the breech block. It is struck by the hammer which has a wedge shaped nose.

If we turn our attention to the arms produced to these patents, I am sure that readers will be surprised at the number of variations produced, mostly it must be said for military trials. Our main sources of reference are the minute books of the O.S.C. The reason for this is quite simple and lies in the fact that the period 1864-70 was one of great advancement in firearms design and one where extensive trials were being carried out to select a new breech-loading rifle for the British army. This culminated in the Government sponsored Breech Loading Rifle Competition 1867; almost every gunmaker/inventor worthy of the title submitted examples of their work. The prestige and financial rewards could be great if successful. It was from these trials that the marriage of the Martini action and the Henry rifled barrel resulted in the adoption of the Martini Henry rifle.

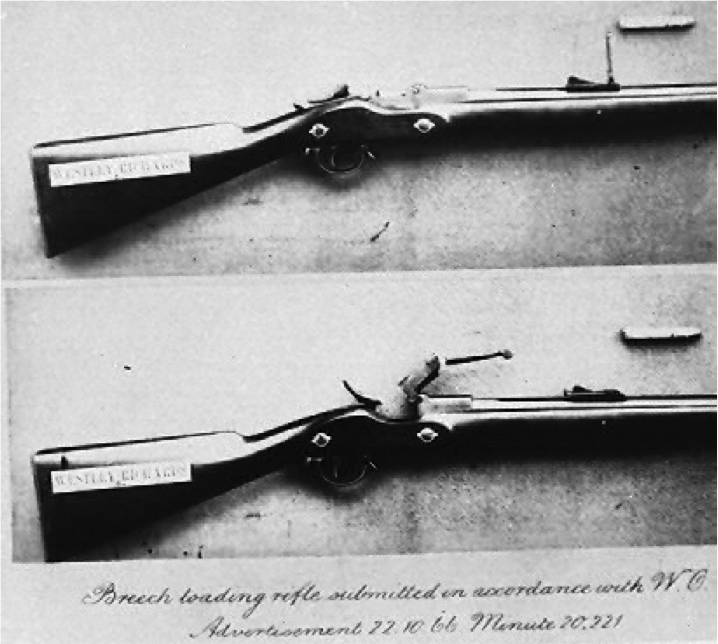

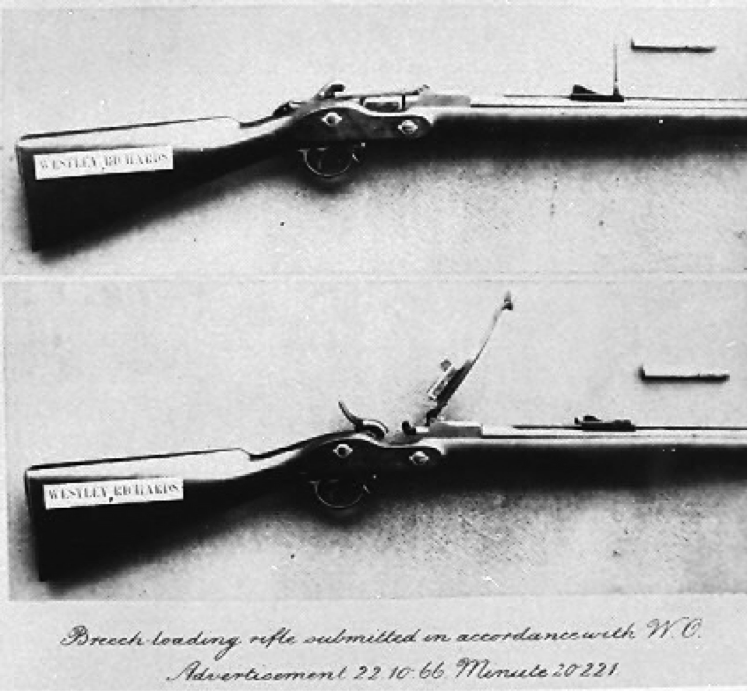

These records tell us that the 1st March 1867 the War Office received from Westley Richards four trial rifles for inclusion in the Government competition. Apparently they were numbered 1 to 4 by their maker the stamp being made on the top of the breech. Rifle No 1 is described in the committee minutes as being adapted from the Monkey Tail but altered to handle centrefire ammunition. In fact the arms was based on patent No 688 with a one piece breech lever, it had a 34” barrel of .45” cal. And rifled with W. Richards octagonal rifling, chambered for a sold drawn brass cartridge. The lock and hammer were fitted to the left side of the rifle, the reason being ease of loading with the right hand, the hammer and lock do not get in the way.

Rifle No 2 differed from No 1 in having the double hinged breech block described in patent No 1960, in all other respects these guns were identical, and chambered for the same cartridge. Rifle No 3 was identical to No 1 but accepted a self-consuming cartridge that did not need extraction. Rifle No 4 was identical to No 2 and like no 3 chambered a combustible cartridge. The whereabouts of these guns is unknown today or even if they have survived the passage of time or the various government amnesties where such treasure have been destroyed. We are fortunate that photos were taken in 1867 for the O.S.C. records have survived and are in the Enfield Pattern Room collection.

Rifle No 2 differed from No 1 in having the double hinged breech block described in patent No 1960, in all other respects these guns were identical, and chambered for the same cartridge. Rifle No 3 was identical to No 1 but accepted a self-consuming cartridge that did not need extraction. Rifle No 4 was identical to No 2 and like no 3 chambered a combustible cartridge. The whereabouts of these guns is unknown today or even if they have survived the passage of time or the various government amnesties where such treasure have been destroyed. We are fortunate that photos were taken in 1867 for the O.S.C. records have survived and are in the Enfield Pattern Room collection.

How did these rifles perform in the trials?. In a word abysmally, through no fault in design, but due to negligence and bad workmanship. Sufficient care had not been taken in their preparation; it was found that rifles No’s 1 & 2 the chambers had been made to small and almost impossible to load. Rifle No 3 was a little more successful initially but in the rapidity trials developed a fault with the striker, first its retractor broke. Then it was discovered the striker had been made too long, on one occasion penetrating the cartridge base further than it should causing a blowback that blew the hammer back to full cock. Rifle no 4 failed because the ammunition supplied was quite unsuitable and not even tried. All four rifles were rejected. The complete failure and rejection of these four arms, for the most basic of reasons must have been a source of great embarrassment to W. Richards, one of the most respected makers of the age. One can only speculate on the fate of the workmen responsible after his return to the Birmingham factory with news of the failure.

In spite of these embarrassing setbacks, W. Richards, a true optimist and professional was not to give up; he promised the O.S.C. that he would send in another batch of trials rifles. The first of these submissions was rifle No 5, an interesting weapon and still in existence today. On examination it appears to be a conversion from a Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle. The conversion was carried out by machining a section out of the breech into which was fitted the double hinged breech unit, the rifle was chambered for the .577” Snider cartridge. It was fired by the hammer driving down a lever connected to a cam that drove the

striker forward. For once this rifle exceptionally well, however like those before it was rejected. The probable reason it offered little advantage over the service Snider and a step backward. A trials rifle No 6, is also known to have survived, it is a .45” centre-fire caliber and has the double hinged breech arrangement. The rifle appears to have never been completely finished and not submitted; I discovered it many years ago on the walls of a pub in Wales, it now resides in the Royal Armouries collection.

The numbering of the next arms submitted broke the pattern of the previous 5, they are numbered 2B, 3B & 11, the reason for this is unknown. Information on these later submissions is limited what is known is rifle No 2B was so marked on the breech block, No 3B also on the breech block and No 11 on both breech and barrel. No 2B is described as having a Whitworth barrel, but was most probably the standard W. Richards octagonally rifled barrel, adapted for the Boxer Eley small-bore cartridge. In trials only 8 shots were fired, however in extracting the cases four heads broke off, these were then withdrawn by the handle of the lever which was detachable for this purpose. Something that is not mentioned with any of the other submission.

Rifle No 3B was of the double hinged design and made to handle special W. Richards designed cartridges. These were made with a short brass base containing the powder charge and a paper jacket end for carrying the bullet. It also failed its trials with extraction problems, which Westley Richards attributed to the manufacture of the cartridges. Rifle No 11 had the one piece lever and used the self-consuming cartridge as No’s 2 an 4 in the earlier trials. It was rejected as the committee considered the ammunition unsuitable for military purpose. It appears all these rifle were variations on those tried earlier and were fitted with left hand locks.

The question now arises did W. Richards produce arms for commercial sale from these designs? The answer is a very positive yes! A few rimfire variation are known to exist, I have seen just two specimen, so I suspect very few were produced and possibly as prototypes or trial guns. If we move on a few years we read in “Wrinkles And Hints To Sportsmen And Traveler’s Upon The Dress, Equipment, Armament And Camp Life” by H. A. Leverson published in 1868, we find an illustrated feature on the commercially available Monkey Tail centre-fire variation.

Mr. Westley Richards has also invented a most excellent central-fire military breech loading rifle, containing the ignition in the cartridge, which promises to supersede all other systems. But notwithstanding that the Duke of Cambridge’s prize has been won for 7 years in succession with rifles of his manufacture, he withdrew it from the competition at the late Wimbledon meeting this year because Mr Henry’s rifle, which is not a military arm, was put in competition with it. Compared with the Snider Enfield it has the advantage of being considerably lighter, the Snider and 60 rounds of ammunition weighing 2 ¾ lbs heavier than the W. Richards rifle.

For rapidity of fire it cannot be surpassed, as twenty shots per minute can easily be fired with it: and its accuracy od shooting is the same as that of his well-known capping carbine (Monkey Tail), which superseded the Terry rifle in the services, and has carried off the breech-loading prize every year since the Wimbledon meeting was first established in 1860, and which up to this time has never been beaten.

For rapidity of fire it cannot be surpassed, as twenty shots per minute can easily be fired with it: and its accuracy od shooting is the same as that of his well-known capping carbine (Monkey Tail), which superseded the Terry rifle in the services, and has carried off the breech-loading prize every year since the Wimbledon meeting was first established in 1860, and which up to this time has never been beaten.

Ammunition

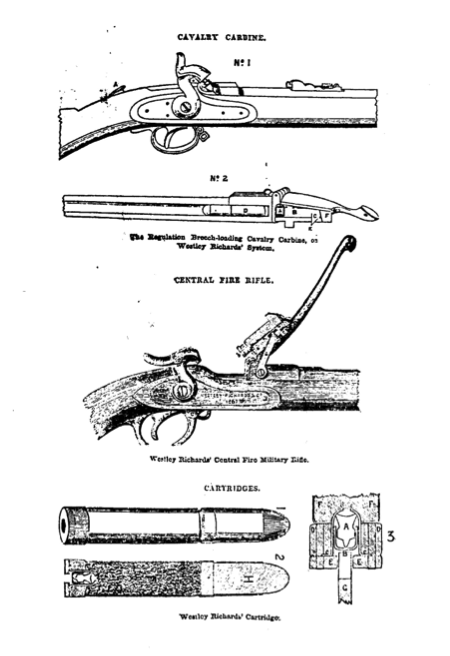

The second illustration shows the system, by comparing it with the first illustration it will be seen that the action is in many ways similar the Westley Richards former rifle. The chief difference being that the sliding plunger is perforated, and containes a needle or striker, that receives the blow from the hammer upon a projecting head, and which sliding forward, explodes the cap contains in a felt wad (third illustration), attached to the cartridge.

These wads are after, insertion of the caps, dipped in tallow and by a very simple arrangement, a portion of this very valuable lubrication agent is driven back by the side of the striker after each discharge, exuding through a hole in the side of the plinger, in regular rotation and keeping every part in good working order.

A very ingenious lever drives back the striker when the action is opened, by lifting up the breech arm: thus all danger of an explosion is avoided while the plunger is depressed. The is no spring in the whole action, which is simple, uncomplicated and in no way liable to get out of order.

Upwards of 10,000 rounds have been fired from one of these rifles without cleaning, scarcely ever missing fire and leaving the arm still fit for work. The cartridges are so simple in their construction that, in case of need, soldiers cam easily make them. The third illustration, fig 1, shows the cartridge ready for loading, fig 2. Is a section of same. Fig 3, shows the action of ignition, in double scale to 1 & 2. G is the striker and strikes the point of an iron anvil which is confined in position by a copper broad flanged cap, at the extremity of which there is an aperture through which the flame is driven and ignites the charge. D- is a soft felt wad, E- a thin one, which are sewn together and keep the flanged cap C and its contents in place. The whole arrangement is very simple and there is scarcely and possibility of a misfire”.

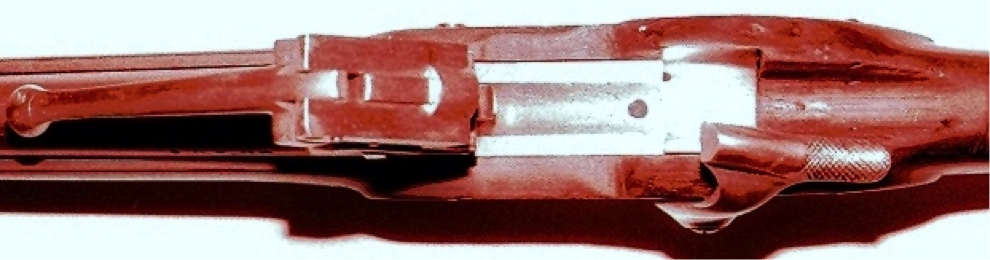

A Rare Example of a Centrefire Monkey Tail Rifle as Detailed By Leverson. Gun No 369

The arm described in Leverson’s book certainly went into limited production and examples are occasionally encountered, but they are exceptionally rare. All known examples follow the pattern of the popular Monkey Tail short rifle, being fitted with a 24” barrel rifled with W. Richards octagonal variant Whitworth rifling. The top of the barrel is stamped “Whitworth Patent” a short carbine ladder sight to 800 yds. is fitted. Brass mounted full walnut stock, stocked to within an 1” of the muzzle; there is one barrel band place 4” back from the muzzle and a cross pin located 7” forward of the breech. A cleaning rod is held in a groove under the barrel as per the normal Monkey Tail. The standard Monkey Tail lock is used fitted with a modified hammer, lock markings being “Westley Richards & Co” and under this the date of manufacture, 1867 to 70 will be encountered. They are all serial numbered in a range of their own and from examination of surviving specimens it seems no more than 600 were made.

The arm described in Leverson’s book certainly went into limited production and examples are occasionally encountered, but they are exceptionally rare. All known examples follow the pattern of the popular Monkey Tail short rifle, being fitted with a 24” barrel rifled with W. Richards octagonal variant Whitworth rifling. The top of the barrel is stamped “Whitworth Patent” a short carbine ladder sight to 800 yds. is fitted. Brass mounted full walnut stock, stocked to within an 1” of the muzzle; there is one barrel band place 4” back from the muzzle and a cross pin located 7” forward of the breech. A cleaning rod is held in a groove under the barrel as per the normal Monkey Tail. The standard Monkey Tail lock is used fitted with a modified hammer, lock markings being “Westley Richards & Co” and under this the date of manufacture, 1867 to 70 will be encountered. They are all serial numbered in a range of their own and from examination of surviving specimens it seems no more than 600 were made.

The following is a list of known surviving specimens:-

Serial Date Location

46. 1867. Royal Armouries.

195. 1868. Weller & Dufty sale.

196. 1868. Wallis & Wallis sale.

319. 1869. S. African collection.

331. 1869. S. African collection.

369. 1870. British collection.

419. 1869. Australian collection.

426. 1869. Enfield Pattern Room

476. 1869. S. African collection.

491. 1869. British collection.

493. 1869. Carmarthen museum.

505. 1869. British collection.

It is interesting that five of the above rifles bear S. African retailers names and others have links to that country, suggesting the majority of production were sold there. There is no doubt that Westley Richards was highly regarded there. Was it a practical arm?. Doubtful it offered any advantage over the standard Monkey Tail; the disadvantages would outweigh the advantages. There would have been problems in home manufacture of the ammunition to a reliable standard, and purchased ammunition would cost little different to metallic and be more fragile.

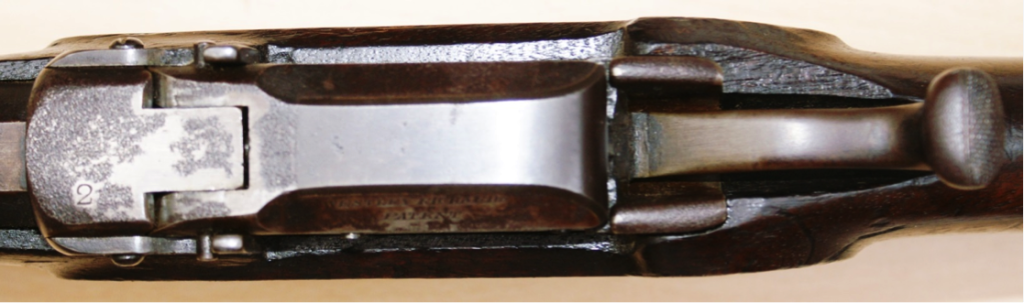

The O.S.C. for various reasons considered the 1867 trials inconclusive and a further series of trials were arranged for 1868. The records are rather confusing but from their report we find that Westley Richards submitted four rifles, two of these were re-submissions rifles No’s 11 and 3B which the committee decided to re-evaluate. The new submissions were of two quite different designs, the first featured what they termed an elevating block somewhat similar to the Martini. Later this would be produced in quantity and be known as the Westley Richards Improved Martini, Gun No 1. The other new submission was described as W. Richards No 2 and there is no mistaking that this is the final Monkey Tail variation a hammerless centrefire rifle and is the gun offered for sale on this list. There is no mistaking it. It is described in the official report as follows:-

“The rifle is adapted for centre fire metallic cartridges. The breech consists of two main parts connected by a hinge, and the whole fastened to by a hinge to the upper part of the shoe, where the barrel is screwed in. The block which closes the breech contains the lock mechanism and pistol (firing pin), the other or tail piece, is the lever by which the action is opened; when shut, this tail piece rests against the curved end of a corresponding curve in the shoe, both struck from a centre below the axis of the rifle and thus making the action secure.

“The breech is opened by raising the tail piece and continuing the motion so as to fold over the barrel the two pieces comprising the action; in so doing the spring which drives the pistol is compressed, and the piston withdrawn. And the extractor caused to withdraw the cartridge case.

“In closing the breech, the block containing the lock mechanism is first lowered and a continuation of the motion shuts the tail piece into place; the rifle is then ready to fire.

The Final Monkey Tail Trials Rifle No 2

In the trials the rifle was fired by Westley Richards’s foreman. It’s first trial was that of rapidity, during which it proved itself capable of 20 rounds a minute, one of the best times recorded for any gun. It then went through the sand and damaged cartridge trials without any problems. The next test was the one for exposure and conducted as follows: A hundred rounds were fired on four consecutive days, and the rifles left in the open exposed to rain or water artificially applied, the breech actions being left alternatively open and closed. After this the rifles were left exposed and still uncleaned for a further four days and nights at the end of which they were fired to ensure they were still serviceable, before being stripped for examination. It was during this trial that the problems with the final Monkey Tail were to occur. The first of these was discovered on firing the first 100 rounds, when it was noticed that the action was becoming rather stiff in operation, but worked well when there was no cartridge in the rifle. The stiffness was therefore attributed to the sizing of the cartridge cases.

In the trials the rifle was fired by Westley Richards’s foreman. It’s first trial was that of rapidity, during which it proved itself capable of 20 rounds a minute, one of the best times recorded for any gun. It then went through the sand and damaged cartridge trials without any problems. The next test was the one for exposure and conducted as follows: A hundred rounds were fired on four consecutive days, and the rifles left in the open exposed to rain or water artificially applied, the breech actions being left alternatively open and closed. After this the rifles were left exposed and still uncleaned for a further four days and nights at the end of which they were fired to ensure they were still serviceable, before being stripped for examination. It was during this trial that the problems with the final Monkey Tail were to occur. The first of these was discovered on firing the first 100 rounds, when it was noticed that the action was becoming rather stiff in operation, but worked well when there was no cartridge in the rifle. The stiffness was therefore attributed to the sizing of the cartridge cases.

After the exposure tests and at the close of this series of trials the breech action was found to have jammed, stripping the arm revealed that the whole action including the mainspring was rusted solid and quite unserviceable. Westley Richards suggested that this problem could easily be solved by the breech parts being steeped in a suitable lubricant. This suggestion was not acceptable to the committee, who responded that the other guns that passed these trials had not been steeped in lubricant.

At this point Westley Richards had had enough and withdrew for the trials, it is here that our story of the Monkey Tail Variations ends. By this time it was quite apparent even to Westley Richards that there were better breech loading systems than a metallic cartridge version of the Monkey Tail. The company went on to perfect the Westley Richards Improved Martini and by 1873 the excellent Deely-Edge falling block rifle. Although he has to be admired for his achievements in adapting the “Monkey Tail” design from its basic form as a capping breech loader through a number of variation including a conversions system for the P53 in both capping and metallic cartridge forms. To become a hammerless centre-fire rifle using a sold drawn brass cartridge case. Surely a tribute to British ingenuity and inventiveness.

At this point Westley Richards had had enough and withdrew for the trials, it is here that our story of the Monkey Tail Variations ends. By this time it was quite apparent even to Westley Richards that there were better breech loading systems than a metallic cartridge version of the Monkey Tail. The company went on to perfect the Westley Richards Improved Martini and by 1873 the excellent Deely-Edge falling block rifle. Although he has to be admired for his achievements in adapting the “Monkey Tail” design from its basic form as a capping breech loader through a number of variation including a conversions system for the P53 in both capping and metallic cartridge forms. To become a hammerless centre-fire rifle using a sold drawn brass cartridge case. Surely a tribute to British ingenuity and inventiveness.

Karl Schlager on April 28, 2014 at 12:53 am

Exellent Article well done

I am a Collector in my possesion are one Monkey Tail Carbine and one sporter Yesterday I was at a Friend of mine (also a Collector) in his Collection is a centre Fire Monkey Tail.

If you want some info please contact me.

Kind Regards

Karl

Willem Crawford on September 16, 2014 at 12:07 pm

I own awestley richards&CO 1874

onley no Ican find is739 barral has been cut to 460 mm

love to know more

John Carter on January 28, 2015 at 12:08 am

I have a Westley Richards Carbine with 20" barrel, S/No 128, the lock marked 1860. under the barrel maked 'T.F' (who is the barrel maker ?) apart from the barrel being stamped .450 (cal?) and another feint 480 there are no other marks.

regards

John

Ivan Alt on June 16, 2015 at 1:29 pm

Hi Guys. I am in possession of a Westley Richards No. 2 Musket or .500/.450 Express cartridge. As the laws in our country are very strict, the previous owner removed the internal working parts and threw them away hoping that the authorities would accept that that would amount to making the rifle "DE-activated". Please assist me to find the missing parts as I am an accredited South African Arms and Ammunition Collectors Association (SAAACA) member. This rifle fits into my collecting theme as it was used during the second Boer War of Independance. Thank you. Ivan Alt (ivanalt@live.co.za)

Jon Huggett on July 9, 2015 at 6:50 am

Hello, I am trying to contact Brian to see if I can use part of his work in a short Booklet I and writing...A couple of years ago Brian published a work called 'A Guide to the Marking of Official Arms of The Rifle Volunteers' and this is the work I'd like to use / reference.

Could you point me in the right direction of how to contact Brian please.

Best Regards, Jon Huggett

Rykie on August 3, 2015 at 2:21 pm

Hi, we have a westley richards think monkey tail with an octagonal barrel. Serial: 6136/lee 2055. I cant find any information on the octagonal shaped barrel. Will send pics. Can you help us with info?

Simon Clode on August 3, 2015 at 2:29 pm

We have no records covering the Monkey Tail rifle by serial number but send us a picture and we will at least see if it is a Monkey Tail and advise what we can!

Thanks

CARLOS VEGA on November 2, 2016 at 7:41 am

yo tengo una con numero de serie 274

Ron Dallaire on March 10, 2019 at 12:50 pm

Good day sirs I am the Care taker of a truely special Presantation monkey tail rifle Marked Isacc Hollis. this is a long range heavy ocatgon barrel with a wide rib on of barrel. It has a 4 leave express style sight plus a ladder sight. it also has sight graduations up to 1200 yards the full length of the barrel and a dove tail to slide an extreme long range sight on it. The stock is made of the pistol grip type & is of incrediblely beautiful walnut withe a metal pistol grip cap. the lock & all other metal is beautifully engraved with small english scroll. the lock has a stocking safety & has I Hollis & sons engraved on it. there is a large patch box on the back of the stock. it has a tiger engraved on it plus gold engraved presentation to a high ranking officer in the Boer Arm. Once i find out who I will let every one know.

Craig W Kinder on April 26, 2022 at 1:27 am

Great article. I have just refurbished a 1862 monkey tail rifle Victorian Volunteer Rifles , Colony of Victoria. Sn 1267.

It shoots fine again after 160 yrs, 50gns 3F, and belted bullet from LEM mould.

Daniël on August 16, 2022 at 1:58 pm

I thought the article would be about mister Wesley but soon enough I discovered that we might be looking at a misnomer of note namely Monkey Tail. This term must have originated amongst the Boer's who called this rifle a "Bobbejaan Boud" directly translated as Baboon derriere relating to the shape of a baboon's behind (as supposed to referencing the buttock only). With any rifle the Boer's flourished but with the English language they were pretty much hapless. Buttock might have been above their translation abilities but the use of Tail correlates very well with "agterent" meaning behind and/or ass which was probably what they were aiming for while conversing in "die rooi taal" - the red language (English).