In 1890, the Cape Colony was busy building railways, Cecil Rhodes was its Prime Minister and Paul Kruger was President of the South African Republic. However, much of the interior was still relatively untamed.

European sportsmen hunting in the 1850s and ‘60s, like Sir Samuel White Baker, favored smooth-bore 4-bore percussion guns firing solid ball for dangerous game. Henry Morton Stanley also carried a single 4-bore when searching for Dr. Livingstone in 1871.

However, with the advent of ‘smokeless’ powders, and rifled breech-loaders beginning to dominate the market in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, smaller calibre rifles began to gain universal acceptance, with nitro-express cartridges in .450, .500 and .577 taking over from the old ‘bore-rifles’. Magazine rifles became more common in the early twentieth century, as did even smaller cartridges, like the .318 Westley Richards, the .275 Rigby and the 6.5 Mannlicher.

Spanning the gap from bore rifles to magazine rifles, the anomaly of the shot and ball gun/rifle is interesting to observe. This jack-of-all-trades enjoyed a spell in the sun; performing as shotgun or rifle according to need. What was it about them that made them so popular with experienced, overseas sportsmen?

Shot and ball guns were not conceived in the breech-loading era. The desire to create one gun that would serve multiple purposes was as attractive and old as the concept of sporting shooting and the need to hunt.

In the days of the musket, a smooth-bored weapon could be loaded with shot or ball as needs dictated. Once rifling became well understood, in the 1860s, rifles became specialist tools, capable of long-range accuracy, while shotguns were separated into specialized bird-shooting or close-range weapons. The characteristic of each differed ever more as the 19th century progressed.

Smooth-bored ‘shot and ball’ breech-loaders continued to be relevant; mostly used as shotguns but capable of firing a heavy ball to defend against attack by large animals, should necessity dictate.

Many special variants of the ‘ball’ proliferated, like the ‘Lethal Bullet’. This was advertised claiming ‘a shotgun can now be used where hitherto it has been absolutely necessary to use a rifle’ and could be used in choke-bored or cylinder bored guns.

Once choke bore became common, after 1875, the standard ‘ball’ for a 12-bore was made 13-bore in diameter to allow it to pass through a gun with some choke, however, many guns of the early choke-bore period are proof stamped ‘NOT FOR BALL’ to warn users against trying to force a 13-bore ball through a 14-bore choke section.

Other options included guns with one rifled barrel and one smooth-bore barrel. These are sometimes referred to as ‘Cape Guns’. The rifled barrel could be a 12-bore, with a 12-bore shotgun barrel alongside, or made for a common rifle cartridge such as .577 BPE, though anything made this way would be less ‘handy’ and well balanced.

1885 was the year that it seemed the ultimate development of the shot and ball gun had arrived. Col. G.V. Fosbery sold his invention to Holland & Holland and they marketed it as a ‘Paradox’. It was a good name for a gun which appeared to be a shotgun but which was also a rifle. The coarsely rifled choke was limited to the last three inches of the barrel and it allowed for the use of shot or conical bullet.

What changed with the Paradox was the accuracy. While shot and ball guns had been very much limited to close-range work, a Paradox was acceptably accurate as a rifle at what most considered proper hunting ranges, of 100 yards or more.

1897 saw the introduction at Westley Richards of the Deeley & Taylor patent ‘hand detachable lock’. Almost universally known as the ‘drop-lock’, this became immediately popular with sportsmen and, when teamed with the Paradox concept, created two models that became firm favourites with Westley Richards customers in India and Africa.

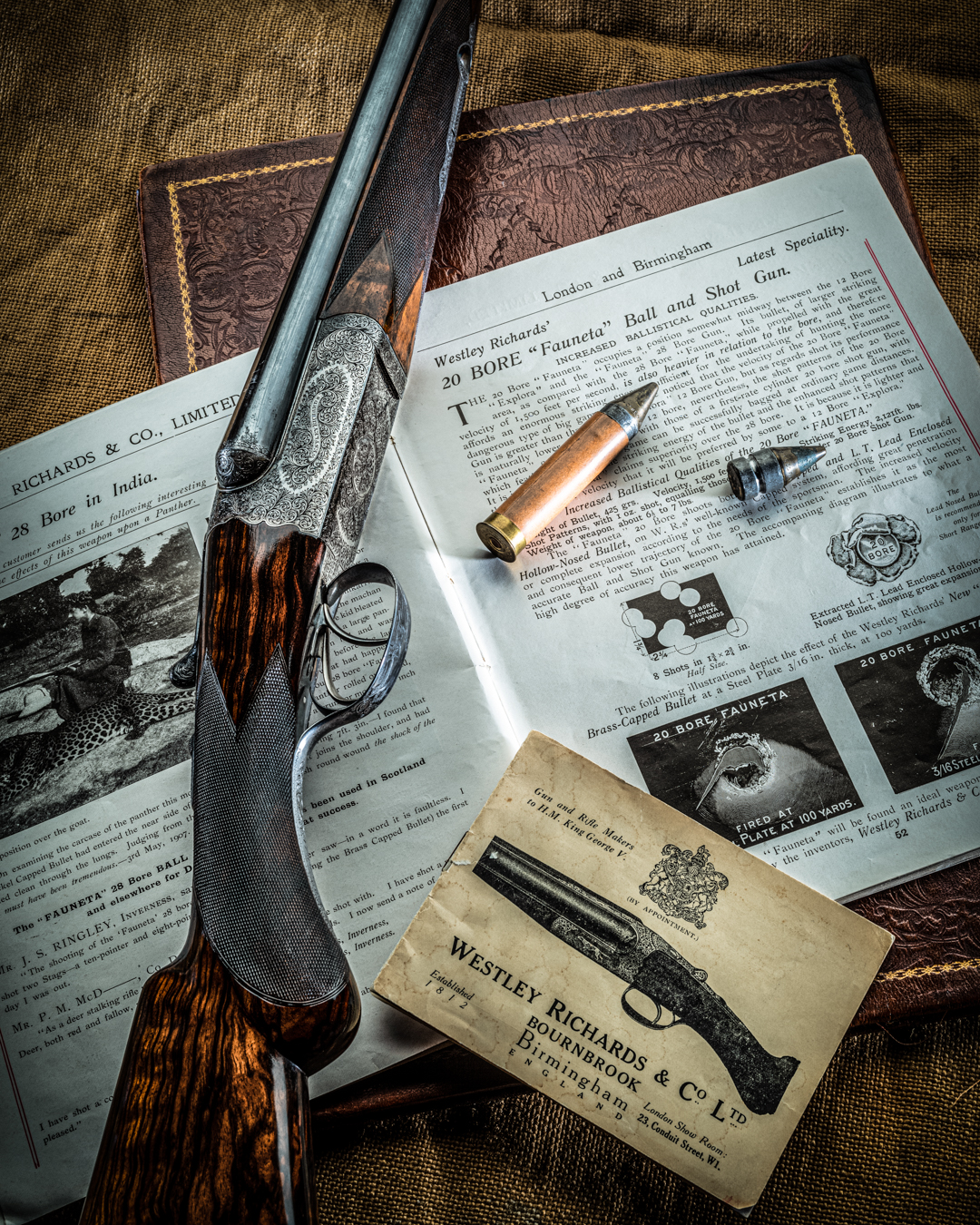

By 1912, the Paradox was no longer patent protected by Holland & Holland and the Westley Richards version was marketed with some vigour in their catalogue. The Explora was the larger version (listed as 12-bore but 8-bores were also made) and the Fauneta, the smaller model, available in 20-bore and 28-bore.

Westley Richards favoured the hand-detachable lock hammerless gun for both these models but also offered a fixed-lock Anson & Deeley patent option. So important were these models considered at the time that they were given fully ten pages in the memorable 1912 catalogue.

Peering back into history, we can see that between 1897 and about 1925 there was a golden moment for the concept of a perfected shot and ball gun/rifle. It delivered just what many hunters desired and Exploras and Faunetas were ordered in good numbers.

They were not a budget option, as a best quality, cased hand-detachable lock Explora, costing seventy pounds, was only five pounds cheaper than a .577 double rifle of the same type.

For those ‘who require a thoroughly sound and moderately priced weapon’ a thirty-nine pound Explora was available, as was a forty-five pound .577. Both were Anson & Deeley ejector models. This price differential is not insignificant.

But just how effective were they? Westley Richards claimed ‘the general handiness of a shotgun but …capable of shooting a bullet accurately and effectively to 300 yards’. That describes a very capable weapon indeed.

The right ammunition was key to the success of these models and Westley Richards sold specially designed shot and ball options. One hundred Explora shot cartridges cost twelve shillings and the same number of brass-capped Explora bullets cost thirty five shillings. Capped bullets for a .577 rifle cost forty-two shillings, by way of comparison.

By claiming to have increased the effective range of the shot and ball gun from 100 to 300 yards, Westley Richards had trebled what Holland & Holland had considered to be the range of the original 12-bore Paradox.

Westley Richards made these claims as early as 1904 and corroborated them with shot groups witnessed by the editor of The Field. At 100 yards, 10 shots were placed into a 5x 3 ½” target, at 300 yards, eight shots into a target 11” x 12”.

As for energy; brass-capped bullets penetrated steel plate one-tenth of an inch thick at 300 yards.

The Magnum Explora’ (and later the Super Magnum Explora) offered even greater performance; made to a weight of 7 1/2lbs and at a price premium of five pounds over the standard model. Testimonials from the period are very fulsome, with experienced hunters recounting their exploits in the field, ‘as accurate as an express rifle and just twice as handy” said one.

Another, attesting to the power and penetration of the brass-capped bullets on a Borneo Wild Ox (called a Tombado) wrote ‘it (the ‘L-T’ capped-bullet) entered his left side behind the shoulder, shattering bones, and passed through his heart and lungs, completely smashing the former, lodging in tissues of the neck – this proves the smashing power you claim’

The smaller cousin of the Explora, the Fauneta, available in 20-bore and 28-bore was very well regarded; being fast-handling like a small bore shotgun but delivering sufficient power and accuracy to handle medium game out to 300 yards.

One testimonial for the 5 3/4lbs 28-bore reads: ‘It will drive your brass capped bullet through hartebeest at 200 yards and kills game up to the size of zebra as well as any other rifle.’

Westley Richards claimed it to be ‘Eminently adapted for many parts of South Africa, for all kinds of buck shooting, for bustard and for use around homesteads. It is so light and well balanced and free from unpleasant recoil that a lady can handle it and shoot it with ease and comfort.’

The 20-bore Fauneta, weighing 6 ½-7lbs drove a 425 grain bullet at 1,500 fps, or 1oz of shot, with patterns equal to those of a good cylinder-bore gun. Accuracy of 8 shots in a 1 ¾”x 2 ¾” target at 100 yards was achievable and penetration of a 3/16” steel plate at 100 yards illustrates its power.

These smaller versions delivered flatter trajectory than the bigger 12-bore Explora, while being sufficiently destructive to be lethal at practical ranges on thin-skinned dangerous game, deer and medium antelope.

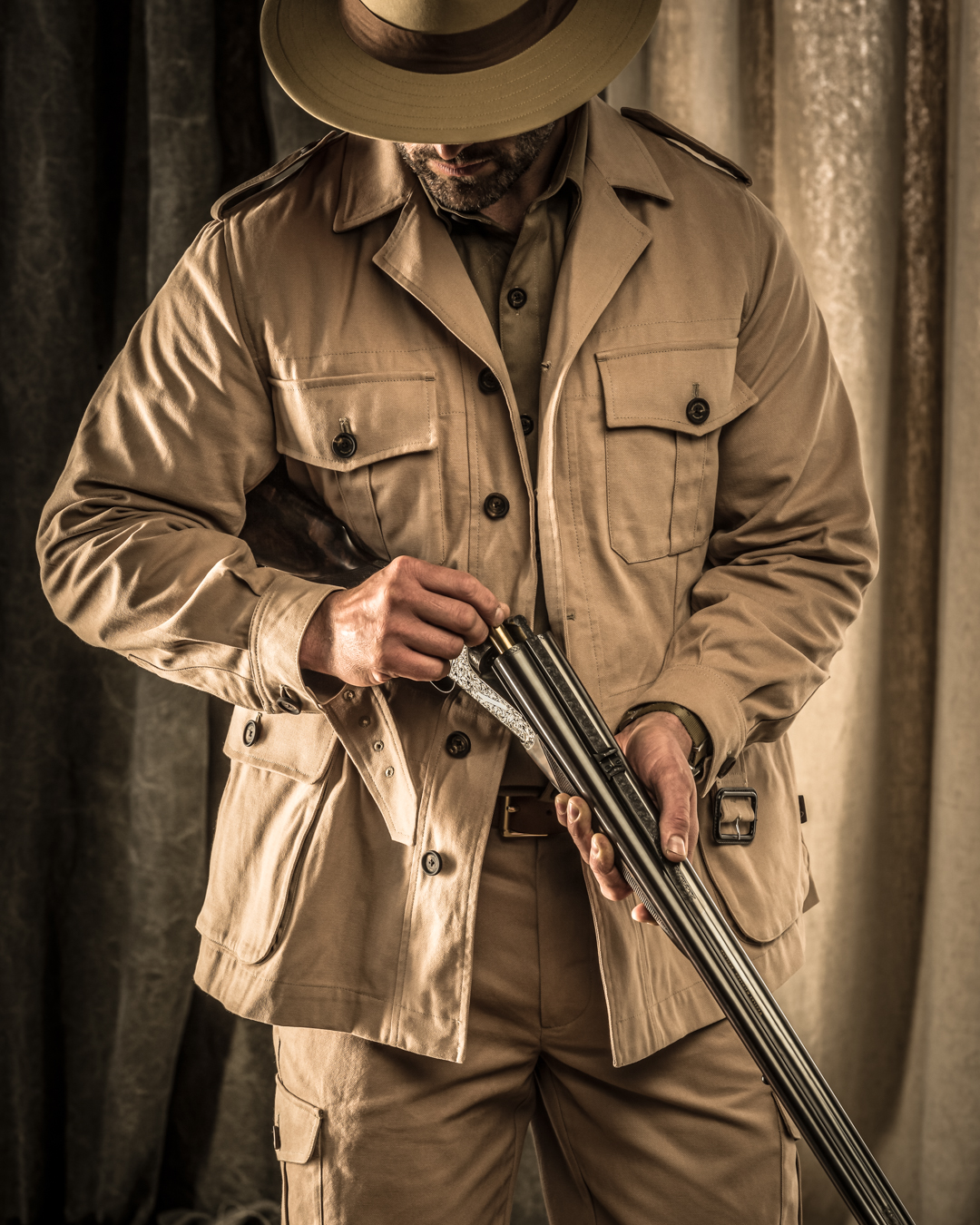

Far from being jacks-of-all-trades and masters of none, these final developments of the shot and ball gun offered the colonial sportsman and adventurer something truly useful and effective: whether called upon to bag birds for the table, protect himself from hungry predators or take an antelope at a trot.

Largely forgotten by today’s safari goers, who prefer double or magazine rifles, they do still make the occasional hunting trip. Silvio Calabi took an 8-bore Explora to Namibia recently to successfully hunt a Cape Buffalo along the Okavango River. He found the experience worthwhile but fully understood how the double 8-bore fell out of favour and nitro express rifles took over.

Many doubles with rifled chokes returned to Britain when the countries of Empire gained independence following the Second World War, and former soldiers and administrators returned home. In England, with little opportunity to utilize them as rifles, many were converted to smooth bore and used as shotguns.

For collectors of sporting guns and rifles, the shot and ball guns that remain make a fascinating alternative to the norm. Experimenting with home-loads to make them shoot as well as they originally did is a challenge. Unfortunately, ‘L-T’ capped bullets are no longer commercially made, and they were very much an essential part of what made the Explora and the Fauneta effective.

In conclusion, one must acknowledge the contribution shot and ball guns made to the lives of late Victorian and Edwardian explorers, colonists and hunters. They were, at least, an effective compromise; performing the duties of shotgun and rifle acceptably well in circumstances where that was all that was required of them.

In their later incarnations, with the better ammunition that was available in the early 1900s, they were very effective rifles, while retaining the capacity to fire shot cartridges.

In fact, the tone of the literature of the time suggests that what started as a concept that would allow a shotgun to shoot ball occasionally, with tolerable effectiveness at short range, became one of a very handy double rifle that could be put into service as a shotgun, if required.

This article was first seen in the summer 2024 edition of African Hunting Gazette - africanhuntinggazette.com

Westley Richards has an outstanding reputation for supplying a comprehensive selection of pre-owned guns and rifles. We pride ourselves on our in depth knowledge of the many sporting arms built over the last 200 years, placing particular emphasis on big game rifles, like the 577 Nitro Express, 505 Gibbs and 425 Westley Richards. Whether looking to grow or sell your collection of firearms, or simply require a trusted evaluation, our team from the sales department would be delighted to hear from you. To view the latest available, head to the used shotguns and used rifles pages, and for those interested in new firearms, explore our custom rifles and bespoke guns pages.

Todd Trombley on July 14, 2024 at 12:51 pm

The shot and ball article was wonderful! One would think that a market exists for this type of gun today. I was wishing for one when hunting in Africa.

George De Siato on July 14, 2024 at 1:45 pm

I congratulate Diggory for his excellent article regarding ball and shot guns. I have a 12 bore Manton that is a ball and shot gun with a Fosbery choke system. Using cast 740 grain slugs of the original pattern and carefully assembled handloads, I am able to keep six (three rights and three lefts) in a 3-1/2 x 5 card at one hundred yards with relative ease. While it has sights for two hundred yards I don't believe I would try it on live game. As to the shot capability, it throws a very even pattern between 1/2 and 3/4 choke. I would like to find some WR Explora ammunition to test. Performance in the field makes me wonder why these guns were not more popular.

Once again, thank you to Westley Richards and Diggory Hadoke for the interesting article and pictures of some very fine WR guns.

Best, George De