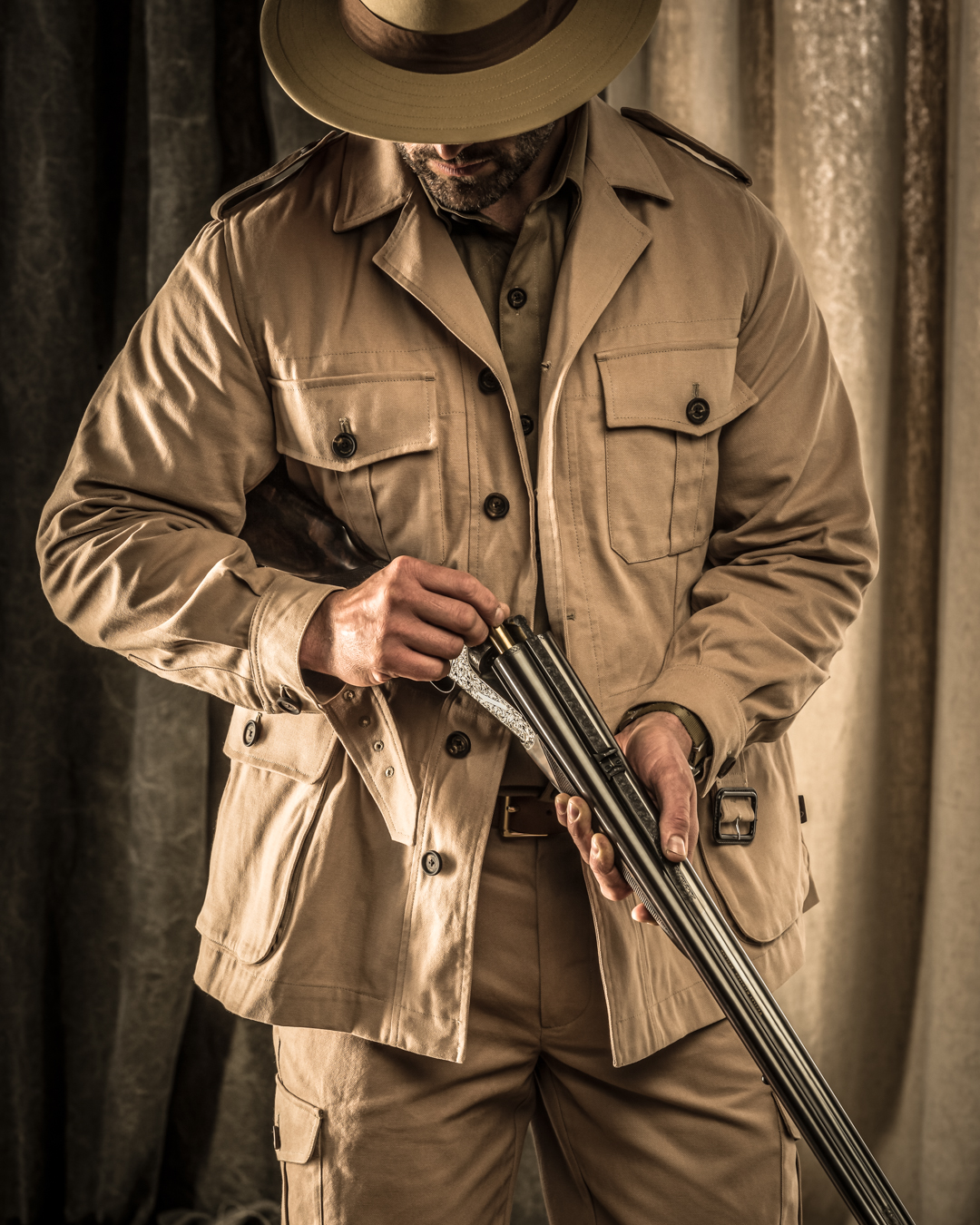

Robin Hurt looking at and considering a recently hung bait.

Robin Hurt looking at and considering a recently hung bait.

The life of modern day professional hunter (PH) is difficult for many of us in the Western world to truly imagine. Most nights are spent around campfires and under canvas a long, long way from home and any modern amenities or creature comforts. Indeed, the African bush becomes their home for anything up to 300 days a year. These are men and women who are more at ease tracking Cape buffalo in thick Mopane forest than they are in a traffic jam or boardroom meeting. Wild, open places under big blue skies are their natural habitat. And there's nowhere they would rather be. It's quite a life and one that may seem otherworldly or anachronistic to many readers. And of course, it has its perils.

Any PH who spends time in pursuit of dangerous game has to have their wits about them at all times; after all, the safety of their clients is their primary concern. But sometimes, even the best and most experienced PHs are caught off-guard. Indeed, almost every year secondhand stories, rumours and half-truths emerge from Africa of close calls or even final curtain calls when dangerous animals have lived up to their reputations. Some of these tales are just that – exaggerated campfire stories that become more dramatic and legendary with each subsequent telling.

But some, as unbelievable as they may sound, are in fact true. I spoke to a number of hunters and guides I have met over the years – all of whom are vastly experienced and have outstanding reputations in their field for their ethics, professionalism and conduct – who have had close calls whilst on safari. This is Robin Hurt's story.

CHEWED BY A CHUI

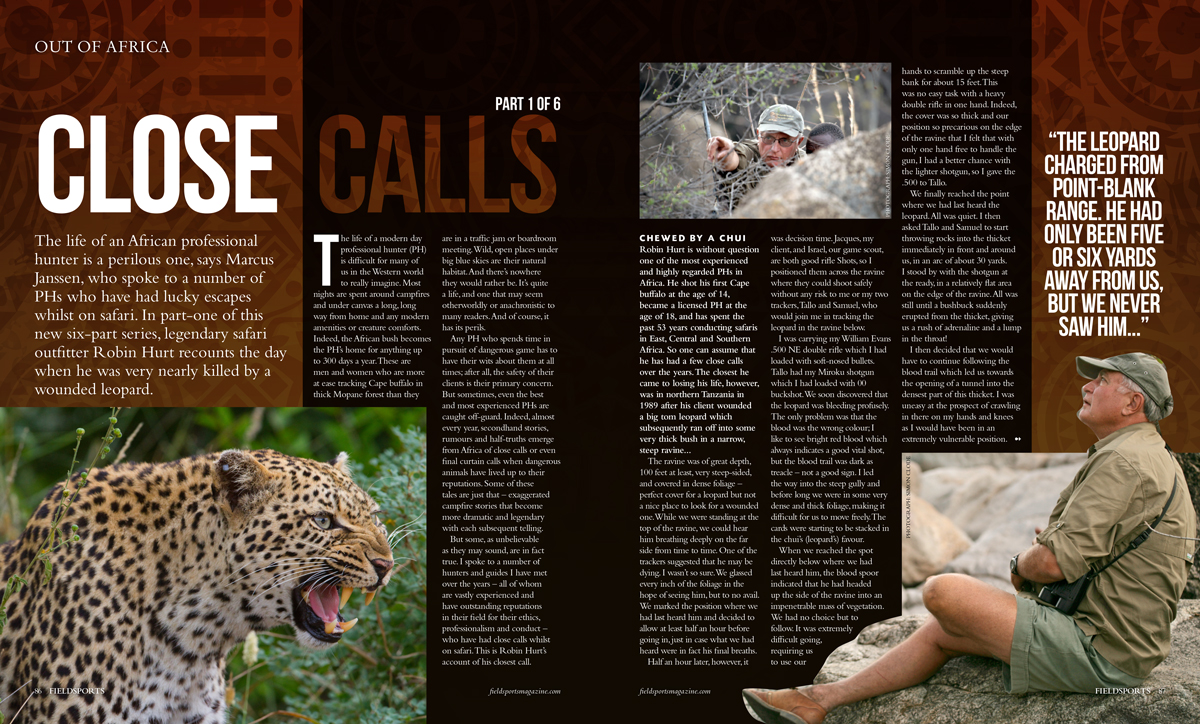

Robin Hurt is without question one of the most experienced and highly regarded PHs in Africa. He shot his first Cape buffalo at the age of 14, became a licensed PH at the age of 18, and has spent the past 53 years conducting safaris in East, Central and Southern Africa. So one can assume that he has had a few close calls over the years. The closest he came to losing his life, however, was in northern Tanzania in 1989 after his client wounded a big tom leopard which subsequently ran off into some very thick bush in a narrow, steep ravine...

The ravine was of great depth, 100 feet at least, very steep-sided, and covered in dense foliage – perfect cover for a leopard but not a nice place to look for a wounded one. While we were standing at the top of the ravine, we could hear him breathing deeply on the far side from time to time. One of the trackers suggested that he may be dying. I wasn't so sure. We glassed every inch of the foliage in the hopes of seeing him, but to no avail. We marked the position where we had last heard him and decided to allow at least half an hour before going in, just in case what we had heard were in fact his final breaths.

Half an hour later, however, it was decision time. Jacques, my client, and Israel, our game scout, are both good rifle shots, so I positioned them across the ravine where they could shoot safely without any risk to me or my two trackers, Tallo and Samuel, who would join me in tracking the leopard in the ravine below.

I was carrying my William Evans .500 NE double rifle which I had loaded with softnose bullets. Tallo had my Miroku shotgun which I had loaded with 00 buckshot. We soon discovered that the leopard was bleeding profusely. The only problem was that the blood was the wrong colour; I like to see bright red blood which always indicates a good vital shot, but the blood trail was dark as treacle – not a good sign. I led the way into the steep gully and before long we were in some very dense and thick foliage, making it difficult for us to move freely. The cards were starting to be stacked in the chui's (leopard's) favour.

When we reached the spot directly below where we had last heard him, the blood spoor indicated that he had headed up the side of the ravine into an impenetrable mass of vegetation. We had no choice but to follow. It was extremely difficult going, requiring us to use our hands to scramble up the steep bank for about 15 feet. This was no easy task with a heavy double rifle in one hand. Indeed, the cover was so thick and our position so precarious on the edge of the ravine that I felt that with only one hand free to handle the gun, I had a better chance with the lighter shotgun, so I gave the .500 to Tallo.

We finally reached the point where we had last heard the leopard. All was quiet. I then asked Tallo and Samuel to start throwing rocks into the thicket immediately in front and around us, in an arc of about 30 yards. I stood by with the shotgun ready, in a relatively flat area on the edge of the ravine. All was still until a bushbuck suddenly erupted from the thicket, giving us a rush of adrenaline and a lump in the throat!

I then decided that we would have to continue following the blood trail which lead us towards the opening of a tunnel into the densest part of this thicket. I was uneasy at the prospect of crawling in there on my hands and knees as I would have been in an extremely vulnerable position.

My sixth sense told me that all was not well.

There was one big branch across the opening of the tunnel, so I asked Samuel to hack it away with a panga (machete).

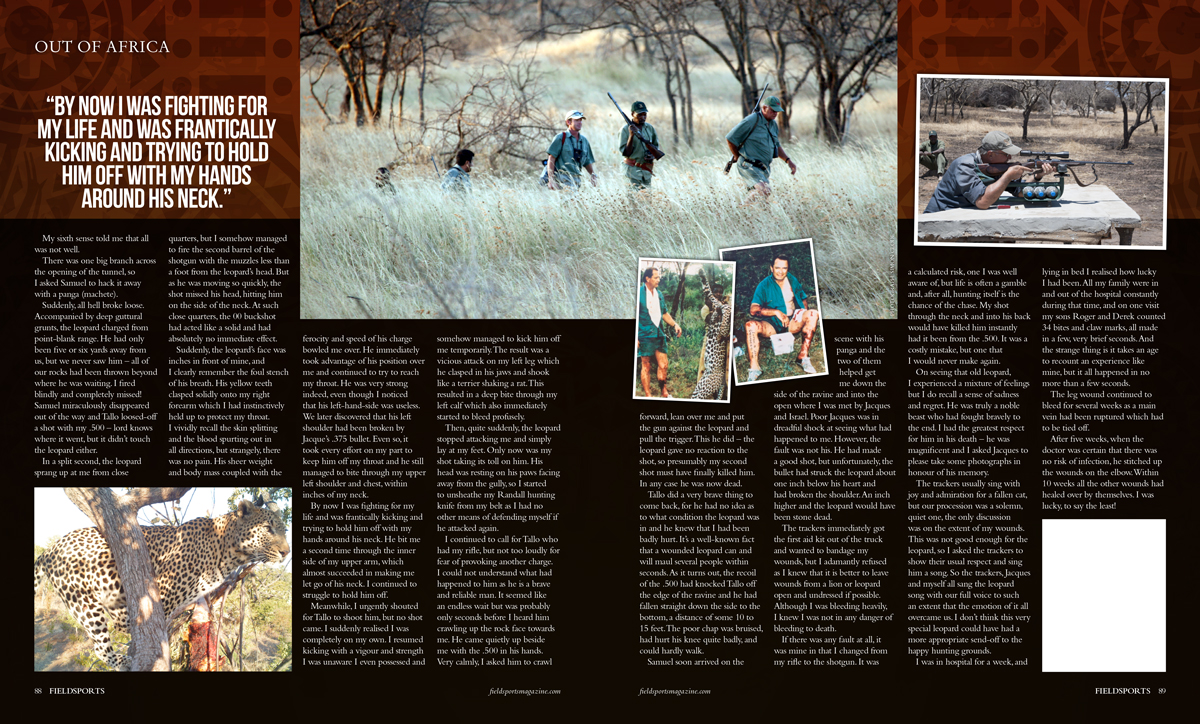

Suddenly, all hell broke loose. Accompanied by deep guttural grunts, the leopard charged from point-blank range. He had only been five or six yards away from us, but we never saw him – all of our rocks had been thrown beyond where he was waiting. I fired blindly and completely missed! Samuel miraculously disappeared out of the way and Tallo loosed-off a shot with my .500 – lord knows where it went but it didn't touch the leopard either.

In a split second, the leopard sprang up at me from close quarters but I somehow managed to fire the second barrel with the muzzles less than a foot from its head. But as he was moving so quickly, the shot missed his head, hitting him on the side of the neck. At such close quarters, the '00' buckshot had acted like a solid and had absolutely no immediate effect.

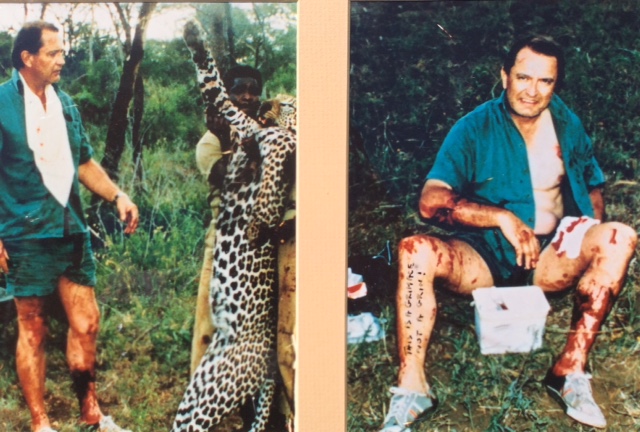

Suddenly, his face was inches in front of mine, and I clearly remember the foul stench of his breath. His yellow teeth clasped solidly onto my right forearm which I had instinctively held up to protect my throat. I vividly recall the skin splitting and the blood spurting out in all directions, but strangely, there was no pain. His sheer weight and body mass coupled with the ferocity of his charge bowled me over. He immediately took advantage of his position over me and continued to try to reach my throat. He was very strong indeed, even though I noticed that his left-hand-side was useless. We later discovered that his left shoulder had been broken by Jacque's .375 bullet. Even so, it took every effort on my part to keep him off my throat and he still managed to bite through my upper left shoulder and chest, within inches of my neck.

By now I was fighting for my life and was frantically kicking and trying to hold him off with my hands around his neck. He bit me a second time through the inner side of my upper arm, which almost succeeded in making me let go of his neck. I continued to struggle to hold him off.

Meanwhile, I shouted for Tallo to shoot him, but but no shot came. I suddenly realised I was completely on my own. I resumed kicking with a vigour and strength I was unaware I even possessed and somehow managed to kick him off me temporarily. The result was a vicious attack on my left leg which he clasped in his jaws and shook like a terrier shaking a rat. This resulted in a deep bite through my left calf which also started to bleed profusely.

Then, quite suddenly, the leopard stopped attacking me and simply lay at my feet. Only now was my shot taking its toll on him. His head was resting on his paws facing away from the gully, so I started to unsheathe my Randall hunting knife from my belt as I had no other means of defending myself if he attacked again.

I continued to call for Tallo who had my rifle, but not too loudly for fear of provoking another charge. I could not understand what had happened to him as he is a brave and reliable man. It seemed like an endless wait but was probably only seconds before I heard him crawling up the rock face towards me. He came quietly up beside me with the .500 in his hands. Very calmly, I asked him to crawl forward, lean over me and put the gun against the leopard and pull the trigger. This he did – the leopard gave no reaction to the shot, so presumably my second shot must have finally killed him. In any case he was now dead.

Tallo did a very brave thing to come back, for he had no idea as to what condition the leopard was in and he knew that I had been badly hurt. It's a well-known fact that a wounded leopard can and will maul several people within seconds. As it turns out, the recoil of the .500 had knocked Tallo off the edge of the ravine and he had fallen straight down the side to the bottom, a distance of some 10 to 15 feet. The poor chap was bruised, had hurt his knee quite badly, and could hardly walk.

Samuel soon arrived on the scene with his panga and the two of them helped get me down the side of the ravine and into the open where I was met by Jacques and Israel. Poor Jacques was in dreadful shock at seeing what had happened to me. However, the fault was not his. He made a good shot, but unfortunately, the bullet had struck the leopard about one inch below his heart and had broken the shoulder. An inch higher and the leopard would have been stone dead.

The trackers immediately got the first aid kit out of the truck and wanted to bandage my wounds, but I adamantly refused as I knew that it is better to leave wounds from a lion or leopard open and undressed if possible. Although I was bleeding heavily I knew I was not in any danger of bleeding to death.

If there was any fault at all, it was mine in that I changed from my rifle to the shotgun. It was a calculated risk, one I was well aware of, but life is often a gamble and, after all, hunting itself is the chance of the chase. My shot through the neck and into his back would have killed him instantly had it only been from the .500. It was a costly mistake, but one that I would never make again.

On seeing the leopard, I experienced a feeling of both sadness and regret. He was truly a noble beast who had fought bravely to the end. I had the greatest respect for him in his death – he was magnificent and I asked Jacques to please take some photographs in honour of his memory.

The trackers usually sing with joy and admiration for a fallen cat, but our procession was a solemn, quiet one, the only discussion was on the extent of my wounds. This was not good enough for the leopard, so I asked the trackers to show their usual respect and sing him a song. So the trackers, Jacques and myself all sang the leopard song with our full voice to such an extent that the emotion of it all overcame us. I don't think this very special leopard could have had a more appropriate send-off to the happy hunting grounds.

I was in hospital for a week, and lying in bed I realised how lucky I had been. All my family were in and out of the hospital constantly during that time, and on one visit my sons Roger and Derek counted 34 bites and claw marks, all made in a few, very brief seconds. And the strange thing is it takes an age to recount an experience like mine, but it all happened in no more than a few seconds.

The leg wound continued to bleed for several weeks as a main vein had been ruptured which had to be tied off.

After five weeks, when the doctor was certain that there was no risk of infection, he stitched up the wounds on the elbow. Within 10 weeks all the other wounds had healed over by themselves. I was lucky, to say the least!

My thanks to Marcus Janssen for allowing me to reproduce this article in full. I have the greatest admiration for Marcus's editorial stewardship of this fine magazine, one which is very well produced and edited with much unique and interesting content. I seriously encourage you to subscribe to the magazine, a move I am sure you will not regret! Subscribe to Fieldsports Magazine here.

Ali on February 13, 2016 at 11:49 pm

Dear Mr. Clode:

You said the results of ban of importing elephant trophies from Africa will be clear in 2015, did it really work? Once you put a great article from R. Hurt here about this topic...

Clayton Bradley Quiah on December 22, 2019 at 4:19 am

I have two questions about Mr. Hurt:

1. The 28 bore which Westley Richards built him... did it have multi choke tubes?

2. Even though he uses a 28 bore for driven grouse , does he still use a 12 bore for waterfowl?

Clayton Bradley Quiah on December 22, 2019 at 4:20 am

I have two questions about Mr. Hurt:

1. The 28 bore which Westley Richards built him... did it have multi choke tubes?

2. Even though he uses a 28 bore for driven grouse , does he still use a 12 bore for water fowl?