When it began to appear on social media sites a decade ago, it caused a bemusing flurry of outrage from people incensed that a rich American would shoot such a rare and precious beast in the name of sport.

That experience might have taught us something about the quickness of finger and slowness of wit of many of hunting’s armchair opponents but it does also raise the subject of dinosaur hunting in the twenty-first century.

Now that the, once endangered, saltwater crocodile of Australia is (since 1974) protected, the Nile crocodile is the closest thing to a dinosaur it is possible to hunt in the wild today.

The Nile crocodile, distributed widely throughout Africa, is the most successful consumer of humans currently inhabiting the planet; with an estimated seven hundred and fifty predations a year, it out-performs sharks, lions, leopards and even the Australian ‘saltie’ when it come to making breakfast out of homo sapiens.

It was while on safari in Tanzania, almost a decade ago, that I was offered the opportunity to try to hunt one of these living fossils from the Rungwa River. We had been in camp for a couple of weeks and my companions and I had been hunting a variety of dangerous and plains game species, with a good deal of success.

As we left Arusha to head for our tented camp, amongst the last news stories that had caught our attention was the growing outcry over ‘Cecil the Lion’. This was to become the cause celebre, of the anti-hunting Twitter mob, of the decade and heralded a concerted effort to destroy sport hunting in Africa by pressure groups from around the ‘civilized world’; mostly peopled by those with no viable alternatives and no actual experience of the wilder parts of the continent.

All this was heating-up, though we remained blissfully unaware, deep in the million acres of hunting-protected game reserve that we came to consider home for the duration of our adventure.

Tanzania is home to roughly half of Africa’s 600,000 crocodiles and the Rungwa River was in the middle of our hunting ground. Minds made up, we set off on a quest for a big one.

Crocodile hunting for us was a game of stealth. The banks of the Rungwa are dry and sandy, with mopane scrub providing a barrier to sight but also useful cover for stalking. We had to work around the problem of the former in order to take advantage of the benefits of the latter.

The ideal scenario is to find a spot where big crocs come out to sunbathe on hot rocks during the day. We spent most of the morning sneaking up to the edge of the cover and peering over the bank to see if we could spot something twelve feet long, lounging in the sun.

It was dry, dusty and hot. Crawling on hands and knees was tiring and dirty work but that was the task we had, so we got on with it. From time to time we might spot a crocodile or a group of them but either they were not of an adequate size or they were not in a situation where a clear shot could be taken.

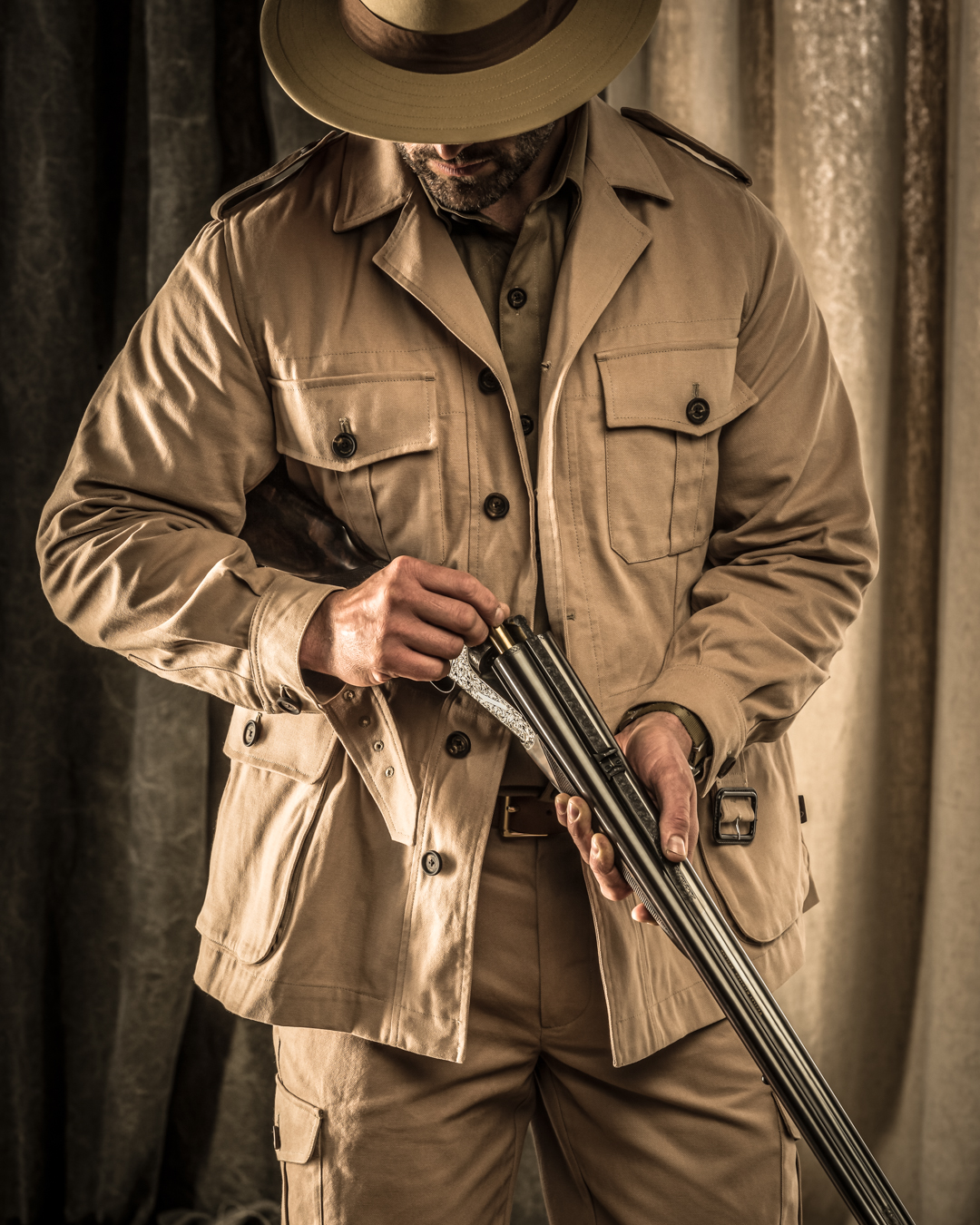

I had armed myself with a double rifle made in 1912 for this hunt. It was made by Cogswell & Harrison and was chambered for the .375” Flanged Magnum cartridge; the double-rifle version of the .375” H&H Magnum.

Loaded with soft-nosed bullets and equipped with a ‘scope, the .375 was a classic choice as part of an African battery and was the smaller of our two double rifles in camp.

We used a .577 Westley Richards drop-lock for close-quarter buffalo hunting later in the trip.

As for other kit, I find it helpful to reflect after a hunt on what worked and what didn’t. Invariably, certain items become staples and others are cast-off. On my feet I had a pair of stout, Hoggs of Fife ‘Rannoch’ boots.

What they lack in delicacy they make up for in comfort, durability and protection. They have been on several African safaris and, though sometimes tempted by other footwear, these are what I always pack and they have yet to let me down.

Teamed with the boots, a pair of leather zip-sided gaiters that I have had forever. They afford protection from snakes, thorns and fallen timber and I would feel naked without them.

My safari jacket was an early version of the Westley Richards Selous jacket, in a light linen material that afforded sun protection and morning warmth without causing over-heating during the day. It has sufficient pockets for essentials and obviated the need to carry a bag.

Under my jacket I wore a light linen safari shirt and a khaki cotton waistcoat with more pockets, from, of all places, Ralph Lauren!

On my head was a ‘Rambler’ foldable trilby from Lock & Co. of St James’s, which, though made from wool felt, is surprisingly cool and comfortable in the sun and provides useful shade with its wide brim.

So, picture all that kit, covered in dust and sand from crawling about in the dirt on my belly trying to get a look at a basking crocodile, and secretly hoping we would not inadvertently crawl into one (or a hippo or a black mamba) while so doing.

After half a day, we did find a spot where the river opened out into a wide section, with exposed rocks in the middle. Peering through the roots, we could see a sizeable group of crocs, with a couple of very big ones, sunning themselves.

We now had our quarry identified and it was time to focus. Biting flies, itchy sand, scratchy thorns; all were put aside.

The thing about crocodiles is, they have a very small brain. It is about the size of a matchbox. Hit the brain and it is lights-out. Miss it and you make a hole in the wrong place; the result of which involves a lot of dangerous follow-up work in murky, crocodile-infested water that nobody will much enjoy, nor thank you for providing.

With that in mind, I slipped two cartridges into the breech of the .375 and belly-crawled down a crocodile–worn indentation in the sand that provided access, through the scrub, to a spot on the bank with a clear line of sight to ‘croc rock’.

The vantage point I had, fortunately, gave me a good angle to take a prone shot down onto the resting crocodile, which was perhaps twenty-five yards distant. I extended my left arm as a rest, impaling it on a big thorn as I did so, though ignoring the pain, with the help of the adrenalin that I was mentally trying to control as the crucial moment neared, I took aim.

Breath control, focus, breathe out, squeeze; then the abrupt crash of the rifle. Before I registered the hit, I re-focussed and drove another soft-point into the chest, just above and ahead of the nearside front leg, then was immediately up on one knee, reloading fast, about to put a third shot down range when Grant, the PH called a halt to proceedings; “He’s dead”.

He was. The huge crocodile remained where he had been spotted, on the rock, now abandoned by his peers, in stark isolation. The spectre of a follow-up hadn’t materialized. Now, recovery was the only pressing task ahead of us.

But first, time to light a cigar and let the moment sink-in. It was an event that will not be repeated in my lifetime and it deserved a period of reflection; the day I went dinosaur hunting on the Rungwa.

The Explora Blog is the world’s premier online journal for field sports enthusiasts, outdoor adventurers, conservationists and admirers of bespoke gunmaking, fine leather goods and timeless safari clothes. Each month Westley Richards publishes up to 8 blog posts on a range of topics with an avid readership totalling 500,000+ page views per year.

Blog post topics include: Finished custom rifles and bespoke guns leaving the Westley Richards factory; examples of heritage firearms with unique designs and celebrated owners like James Sutherland and Frederick Courtenay Selous; the latest from the company pre-owned guns and rifles collection; interviews with the makers from the gun and leather factory; new season safari wear and country clothing; recent additions to our luxury travel bags and sporting leather goodsrange; time well spent out in the field; latest news in the sporting world; and key international conservation stories.