A “Lion Tax” to support wildlife conservation sounds intriguing. In October 2023, The Conversation published the results of a test carried out to see whether visitors to South Africa - many of whom spend part of their holiday taking photos of animals in national parks - would pay a “lion protection fee” at border entry points. The authors of the study, three wildlife-research academics, wrote, “Our idea was that this could compensate for any lost revenue from trophy hunting were it to be banned.”

Tourists viewing lions in Kruger National Park area, South Africa.

Tourists viewing lions in Kruger National Park area, South Africa.Wherever it is allowed, hunting can provide employment and organic meat, and help drive conservation. To some people, however, killing animals for recreation (as opposed to subsistence hunting) is distasteful, especially when it’s labeled trophy hunting. But over the past century, recreational hunting has also evolved into an important source of funding for wildlife management, aka conservation. With this in mind, concerned parties on both side of the hunting question are exploring ways to raise money for conservation that do not involve killing wild animals. Hence the concept of a Lion Tax.

The Need

All wildlife, not just huntable species, require clean water, clean air, natural food and habitat in which to shelter, forage, migrate and breed. In many parts of the world, if hunting disappears, corresponding public and private financial support for all wildlife would disappear with it—as would a major incentive for conservation. Many thousands of jobs would disappear as well.

By the early 20th Century, hunters were facing this dilemma from the other side: If wild animals disappear—which was beginning to happen at an alarming rate—there can be no more hunting, for subsistence or for recreation. In North America, for example, overhunting had reduced the bison from tens of millions of animals to a few hundred; the passenger pigeon, three to five billion of which were thought to exist before Europeans arrived, were wiped out entirely; and the harvest of ducks and geese for the restaurant trade and egrets, swans and herons for their plumage (for ladies’ hats) was rapidly decimating those species. White-tailed deer and wild turkeys were under similar pressures, as were popular species of gamefish.

Mass hunting of waterfowl in the United States.

Mass hunting of waterfowl in the United States.A handful of American politicians and naturalists and then wealthy members of hunting and fishing clubs inspired innovative federal legislation that not only protected wildlife from overhunting but also opened up the money taps. It began with the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which installed federal protections for more than 1,000 species of migratory birds across North America.

Funding

Conserving wildlife requires habitat preservation and restoration, research, planning, implementation and enforcement; all are expensive. To generate these funds in the US, the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act of 1934 requires waterfowl hunters to buy a national duck stamp and the Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937, or Pittman-Robertson Act, imposes an 11% tax on the sale of firearms, ammunition and archery equipment. The Dingell-Johnson Act, or Sport Fish Restoration Act of 1950, does the same thing on behalf of gamefish.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service lumps such legislation together into the Wildlife and Sportfish Restoration Program, a public-private partnership that has raised, since 1937, approximately $25.5 billion for wildlife and habitat conservation—money that makes up about three-quarters of state fish & wildlife agencies’ annual budgets. By law, the funds cannot be diverted to other purposes.

Other countries, which may have been industrialized for longer or are more densely settled, smaller, poorer or governed differently, pay for wildlife conservation by different means. Nonetheless, whether through income taxes, concession and permit fees, private donations to organizations, or surcharges and other levies paid to governments by hunters, globally hunting generates enormous sums of money for conservation. As well, landowners who sell the opportunity to hunt their game manage their properties for the benefit of wildlife.

Alternatives to hunting?

To replace hunting, then, as a means and motive for conservation is a tall order. But there are possibilities—such as the Lion Tax suggested as a “non-consumptive” way of funneling cash to conservation. Of 907 visitors to South Africa the authors said they interviewed, 84.2% reportedly stated that being charged a “lion protection fee” was a “great” or a “good” idea. They then calculated that charging $3 to $7.40 per tourist per day for up to six days could bring in as much or more than the

$176.1 million presently generated annually by recreational hunting in South Africa. (Fees are in US dollars.)

Other research found that trophy hunters spend much more than that in South Africa, and that hunting supports 17,000 jobs there—which the Lion Tax presumably would erase. In their responses to the Lion Tax article in The Conversation, South African readers pointed out that such a tax would simply disappear into the government’s general fund while the lucrative business of trophy hunting would be allowed to continue. (It was also pointed out that the very few wild lions currently hunted in South Africa are invariably on “destruction permits” as escapees or livestock killers, so the Lion Tax would save no lions.)

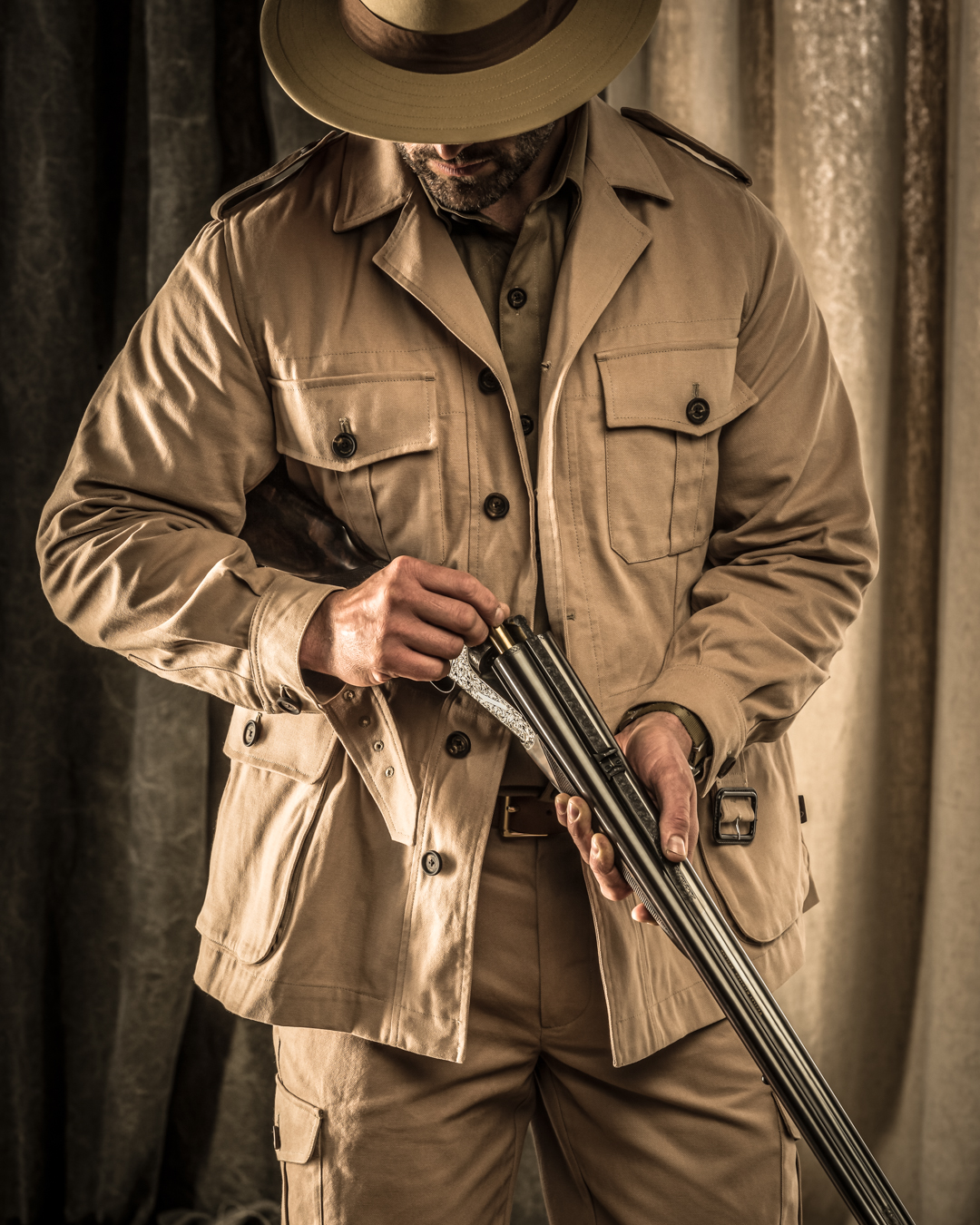

Hunter in Africa. Source: Alamy

Hunter in Africa. Source: AlamyWildlife tourism

Photo-tourism, which would help feed such a Lion Tax, is often posited as a replacement for hunting that creates jobs and brings in revenue while preserving the lives of animals. This ranges from multi-day wilderness tours to day visits to wildlife preserves and national parks. An African game-viewing safari in 5-star accommodations is expensive; a daily fee at a national park anywhere generally amounts to pocket change.

Tourists observing lion in Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. Source: Alamy

Tourists observing lion in Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania. Source: AlamyEntrance fees at national parks contribute toward the parks’ operating expenses, which include (but aren’t limited to) conservation work; a park that supports no wildlife will see few visitors. Eco-safari operators may pay conservation fees directly to government or taxes that contribute to conservation programs.

However, to call this kind of wildlife tourism “non-consumptive” can be misleading. Animals are not killed, but they and their habitat are intruded upon. Studies show that even a few human visitors to remote national parks affect the wildlife there. And in more accessible wildlife regions, tourist camps or lodges may dot the landscape, each seeing hundreds of visitors in season. This means more jobs for local people, but the food and supplies that must be trucked in and waste that is burned or trucked out, as well as fuel for vehicles, kitchens and generators, is significant. Cycling that many people through a camp may also require better roads and perhaps airstrips and bridges; it also leads to substantially more traffic and noise in once-wild areas. Funds raised for conservation aside, these are significant challenges to sustainability, biodiversity, restoration and preservation.

Hunting operators point out that they have fewer clients and that their camps may be the only ones in hundreds of thousands of acres of wild areas that otherwise might be unprotected; and that, because their fees are higher, they contribute more to conservation. However, global wildlife tourism is expected to grow from $128 billion in 2021 to around $220 billion by 2032. Given sufficient political will and the support of voters, some portion of this could be appropriated specifically for conservation.

Tax incentives

In November 2023, South Africa’s Dept. of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment announced the country’s first tax incentive for threatened species. This will allow any taxpayer—a private landowner, a trust or a company—protecting threatened ecosystems or species to deduct from their taxable income the costs of their conservation efforts. The immediate beneficiaries are likely to be the owners of the 8,000 or so rhinos in private herds in South Africa, which are not hunted. (One of them told me that he spends 1.5 million rand, $80,000, annually on ex-military armed guards to protect his 13 rhinos from poachers.)

Armed guards protect rhinos in Kenya. Source: Alamy

Armed guards protect rhinos in Kenya. Source: AlamySimilar governmental incentives for conservation are emerging around the world; many of them are conservation easements geared toward reducing the taxes on money earned on protected lands, usually from low-impact, sustainable uses such as organic farming, specialized tourism and, sometimes, hunting.

The world’s bankers also have recognized the link between money and conservation. A group called theSustainable Finance Coalition worked with South Africa’s DFFE to create the threatened-species tax incentive; its stated mission is to create “finance solutions for enduring naturescapes” and its goals are to conserve 100 million hectares (247 million acres), benefit 100,000 people and “unlock” $500 million in conservation funds by 2030.

In 2022, the US Congress passed conservation-funding legislation that is not hunting-dependent. RAWA, the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, provides money and expertise to states for conservation. The bill established the Endangered Species Recovery and Habitat Conservation Legacy Fund and an Endangered Species Recovery Grant Program, both intended to be stocked by fees and penalties for violations of environmental regulations.

Lotteries

In the US, the nonprofit Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, essentially a hunting and fishing organization, now promotes state lotteries as additional sources of funding for conservation, pointing to the “rising costs for natural resource management and increased public utilization of these resources.” Arizona, Minnesota, Colorado and Oregon presently dedicate part of their lottery earnings to conservation of public lands and waters. These are untethered to hunting. In the UK and across Europe, national lotteries working with the European Commission, Rewilding Europe, the European Investment Bank and many other official and non-governmental organizations are also funneling money to conservation. Beneficiaries of specific campaigns include bears, wolves, vultures, bison and pelicans.

Cautions

In hotspots such as Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve, Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater and Uganda’s gorilla reserves, wildlife tourism has doubled or tripled in the past 15 years (with 18 months or so off for COVID-19). The crush of sightseeing vehicles on the banks of Kenya’s Mara River during the famous wildebeest crossing has become so thick that it can interfere with the migration. In the US, Yellowstone National Park reported a record 4,860,242 visitors in 2021; bison gorings and bear attacks on visitors are becoming almost common.

‘Bear jam’ in Grand Teton National Park, United States. Source: National Park Service

‘Bear jam’ in Grand Teton National Park, United States. Source: National Park ServiceEven outside such popular, accessible wildlife reserves, biologists fear that rampant nature tourism is altering the behavior of wild animals, with implications for feeding, breeding, migration, predation and conservation. And in non-tourist areas, researchers point out that, aside from the financial impacts, banning hunting can open up millions of acres of wilderness to farming, mining, logging, drilling for oil and gas and other forms of development, as well as increased poaching.

Solutions

As human populations balloon and civilization becomes always more complex, regulators have learned, or should have learned, that blanket legislation rarely succeeds; one size does not fit all. A thousand wild ecosystems around the world may require nuanced variations of a hundred management regimens, each carefully tailored to a specific set of circumstances and goals—always reinforced by ongoing scientific analysis and backed up with the consent of informed citizens.

The financial needs of each of these ecosystems should be supported by some combination of the funding mechanisms listed here, and others still to come. Excise taxes, tax incentives, investment funds, charitable donations, conservation easements, lotteries and revenue from wildlife tourism, including hunting, are tools in the conservation toolbox, each selected for best use in a given scenario.

This article was contributed by Conservation Frontlines. Conservation Frontlines’ content is produced in collaboration with Michigan State University’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. Together, they report on the most important sustainable use conservation and wildlife management news from North America and around the world. https://www.

The Explora Blog is the world’s premier online journal for field sports enthusiasts, outdoor adventurers, conservationists and admirers of bespoke gunmaking, fine leather goods and timeless safari clothes. Each month Westley Richards publishes up to 8 blog posts on a range of topics with an avid readership totalling 500,000+ page views per year.

Blog post topics include: Finished custom rifles and bespoke guns leaving the Westley Richards factory; examples of heritage firearms with unique designs and celebrated owners like James Sutherland and Frederick Courteney Selous; the latest from the company pre-owned guns and rifles collection; interviews with the makers from the gun and leather factory; new season safari wear and country clothing; recent additions to our luxury travel bags and sporting leather goodsrange; time well spent out in the field; latest news in the sporting world; and key international conservation stories.