An adult male Gobi bear in the Great Gobi A Strictly Protected Area, Mongolia, photographed with a remote camera c. 2015. (Photo & Cover Photo: Joe Riis)

An adult male Gobi bear in the Great Gobi A Strictly Protected Area, Mongolia, photographed with a remote camera c. 2015. (Photo & Cover Photo: Joe Riis)The Gobi Desert in central Asia comprises about half a million square miles (1.3 million square kilometers) within southern Mongolia and extending into northern China as well. The region is desolate, with year-round temperatures that range from -40° to 104° Fahrenheit (-40° to 40° Celsius) and extremely meager precipitation. Annually, rain and snow typically range from just 0.8 of an inch to 4.0 inches (20 to 100 mm) and in some years no rain or snow falls at all. Such a harsh environment is challenging for animals and wildlife population densities are much lower than in more fertile areas. Nevertheless, the Gobi is home to spectacular animal life including wild camels, wild asses, gray wolves, snow leopards and saker falcons, the national bird of Mongolia.

Of the desert’s wildlife, the rarest is the Gobi bear, locally known as Mazaalai. Though there is debate among scientists whether the Gobi bear is a subspecies or a distinct population of brown bears, it is quite possibly the world’s most endangered bear. The data are imprecise, but over the past 50 years the estimated number of Gobi bears has ranged from 17 to 52 individuals; over the past 10 to 20 years, their population has been presumed stable at about 40 to 50 bears.

Although Gobi bears are occasionally reported in China, their current known range is only in the Great Gobi A Strictly Protected Area, part of a two-zone (A and B) wildlife sanctuary within southern Mongolia’s Great Gobi Biosphere Reserve.

Known range of Gobi bears in Mongolia. The Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area lies farther west; it has no bears and is managed separately. (Map: Maggie Smith, National Geographic Society)

Known range of Gobi bears in Mongolia. The Great Gobi B Strictly Protected Area lies farther west; it has no bears and is managed separately. (Map: Maggie Smith, National Geographic Society)A decade ago, the President of Mongolia declared 2013 to be the Year of the Gobi Bear, the first time a nation has made such a decree for any bear, and the Gobi bear was proclaimed a national treasure. This was intended to raise awareness and to spark conservation efforts. Because so few bears exist, and in such a challenging environment, the Mongolian government considers the Gobi bear critically endangered and on the brink of extinction, and is working to ensure the population survives and thrives into the future.

Conservation efforts so far have focused on identifying threats to the bear. Climate change, for example, has made deserts such as the Gobi even hotter than before. Higher temperatures could impact the growth and abundance of already limited important foods of the Gobi bear such as wild rhubarb and Nitraria, a group of shrubs that produce edible berries. Gobi bears also will eat insects such as grasshoppers, which are sometimes abundant in the desert, but unlike the brown bears of North America and Europe, Gobi bears apparently eat little meat or fish. Their diet and the scarcity of food undoubtedly influences the body size of Gobi bears, which are smaller than most other brown bears. A healthy and large adult male Gobi bear captured in spring 2023 weighed only 300 pounds (135 kilograms).

The Great Gobi A is relatively well protected from adverse human influence. Like many other protected areas worldwide, the A Reserve is surrounded by a large (3,900 square miles; 10,100 square kilometers) buffer zone that allows only limited human activity. People cannot live permanently within this buffer zone, but nomadic herders are allowed to graze their livestock—sheep, goats, horses and camels—in the zone from 10 November to 25 February each year.

Domestic goats and sheep grazing in the Great Gobi A buffer zone. (Photo: Andreas Zedrosser)

Domestic goats and sheep grazing in the Great Gobi A buffer zone. (Photo: Andreas Zedrosser)Herders bring their animals into the zone to take advantage of fresh forage. However, livestock numbers entering the zone have increased dramatically in recent years. Mr. Ch. Bayarbat, Director of the Great Gobi A, estimates that as many as 1 million domestic animals, predominantly goats and sheep with some camels, now graze in the buffer zone each year. In addition, herders sometimes move in before the authorized period begins and stay after it legally ends. Director Bayarbat believes that greater livestock grazing pressure could reduce the abundance and availability of the plant foods needed by Gobi bears.

To grow trade and build the regional economy, Mongolia has expanded mining near the Great Gobi A. Extraction of gold and other metals is accelerating, and Mongolia also mines coal nearby for sale to China. With this increased activity plus the re-opening of China’s border after the Covid pandemic, the number of trucks traveling between Mongolia and China has increased also.

Furthermore, a new railroad has been proposed alongside the road to expand the shipment of coal and other commodities even further. This transportation corridor, as well as another road west of the Great Gobi A, could become barriers limiting the bears’ ability to expand their habitat. Gobi bears are not migratory, but very large areas of desert—sometimes more than a thousand square miles, almost 2,600 square kilometers—are required to produce enough food and other resources to sustain a single bear.

A Gobi bear in its “challenging environment.” (Photo: Joe Riis)

A Gobi bear in its “challenging environment.” (Photo: Joe Riis)Another threat is the illegal use of the Great Gobi A by small-scale miners who carry in their equipment on motorcycles or other small vehicles. The World Bank estimates that the annual income in Mongolia is 10 million Tugriks, only about US$4,000; since the price of gold currently hovers around US$1,915 per Troy ounce, it is not difficult to understand why people trespass in the Great Gobi A. The threat to the bears isn’t so much where mining takes place, but rather that miners often camp near the Gobi’s scarce water points, which likely prevents bears (and other wildlife) from accessing this critical resource.

According to Director Bayarbat, Gobi bear conservation’s most pressing need is financial—that is, funds to buy motorcycles and other vehicles as well as better radio gear, all to improve game rangers’ ability to patrol the Great Gobi A and enforce wildlife laws and regulations.

In contrast to the case of many other bear populations around the world, even elsewhere in Mongolia, there are virtually no controversies or conflicts surrounding Gobi bears. As these bears eat mostly plants, attacks on livestock are essentially unheard of. Also, because of the vanishingly small number of Gobi bears and the fact that their desert is largely uninhabited by people, bear raids on human garbage dumps are nonexistent. The only conflict recently reported to government rangers was one instance in the buffer zone where a bear was observed eating feed put out for the herder’s goats and sheep.

In 2022, Mongolia announced new efforts to conserve the Gobi bear and the President, Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh, made conserving the species one of his administration’s top three environmental priorities. Altansaruul Oyunbileg, Chief of the Environmental Projects and Programmes Unit within the Office of the President, recently said that a draft conservation plan for Gobi bears will be finalized by the end of 2023. He described it as a multifaceted approach that will include improved monitoring of the bears, possibly overpasses to allow the bears and other wildlife to cross roads and railroad tracks, and attempts to remediate the effects of climate change. Implementing such a plan will be critical to the long-term protection and survival of the Gobi bear.

Dr. Jerrold Belant is the Editor-in-Chief of Conservation Frontlines and the Boone and Crockett Chair in Wildlife Conservation at Michigan State University. He holds degrees in wildlife biology and natural resources from the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. https://www.conservationfrontlines.org/

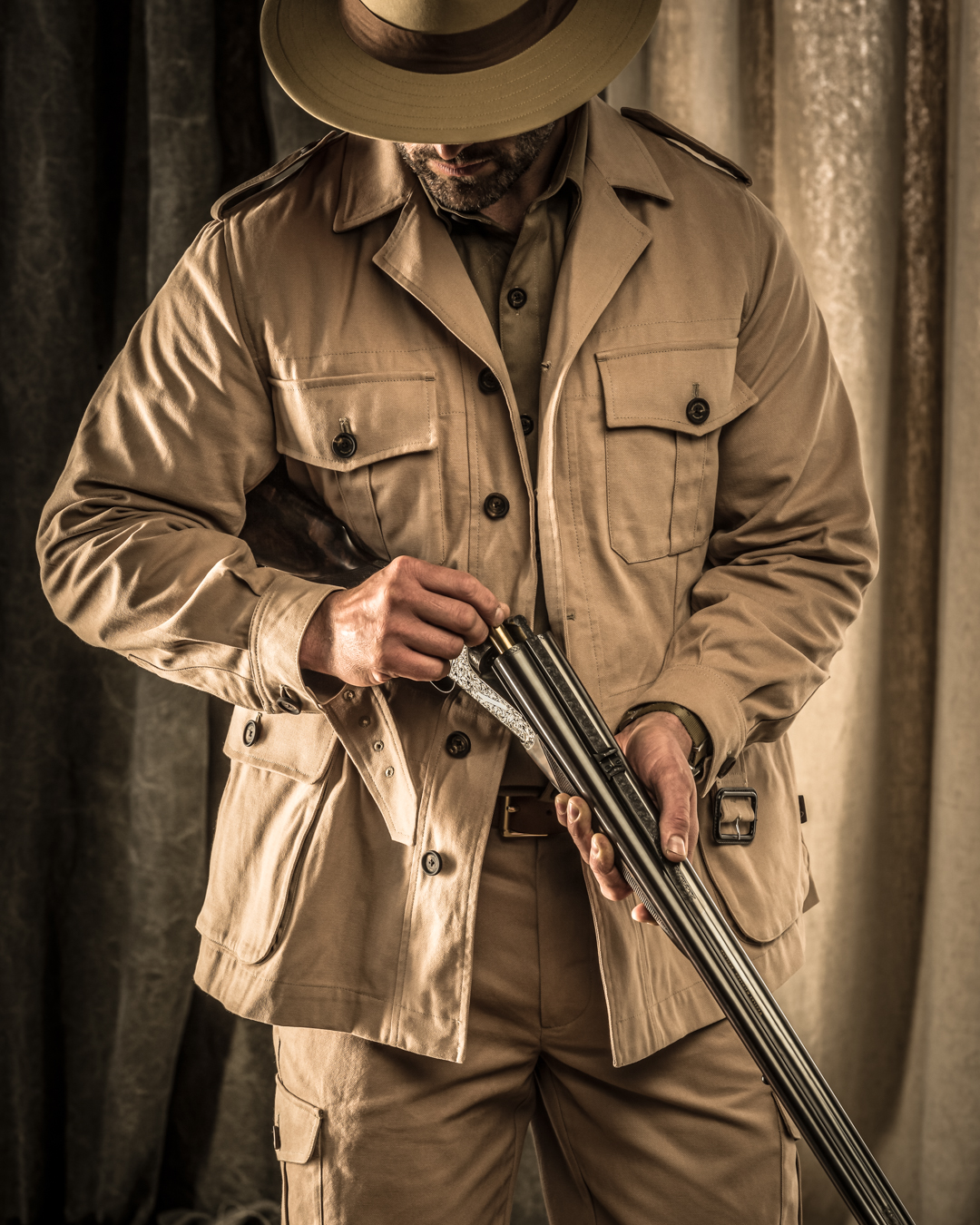

The Explora Blog is the world’s premier online journal for field sports enthusiasts, outdoor adventurers, conservationists and admirers of bespoke gunmaking, fine leather goods and timeless safari clothes. Each month Westley Richards publishes up to 8 blog posts on a range of topics with an avid readership totalling 500,000+ page views per year.

Blog post topics include: Finished custom rifles and bespoke guns leaving the Westley Richards factory; examples of heritage firearms with unique designs and celebrated owners like James Sutherland and Frederick Courtenay Selous; the latest from the company pre-owned guns and rifles collection; interviews with the makers from the gun and leather factory; new season safari wear and country clothing; recent additions to our luxury travel bags and sporting leather goodsrange; time well spent out in the field; latest news in the sporting world; and key international conservation stories.